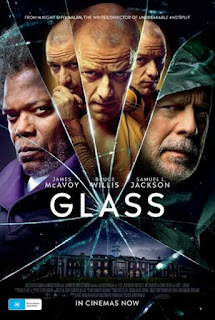

The unconventional superhero film Glass, written and directed by M. Night Shyamalan, unites in a Philadelphia mental institution three characters from his previous films: good guy David Dunn/the Overseer (Bruce Willis) from Unbreakable (2000), bad guy Elijah Price/Mr. Glass (Samuel L. Jackson) also from Unbreakable, and ambiguous guy Kevin Wendell Crumb (along with his many personalities) (James McAvoy) from Split (2017). Psychiatrist Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson) wants to convince them that they’re all suffering from delusions of grandeur. They are not superheroes, she argues, but rather ordinary people who’ve unconsciously manipulated their perceptions of reality to convince themselves of having superhuman capabilities.

Supergenius mass murderer Mr. Glass, so called for the brittleness of his bones, is wheelchair-bound and near catatonic due to the drugs in his system. David, quiet and stoic, merely wants to get out (while avoiding his weakness of water) so he can continue his brand of vigilante justice. The true standout is Kevin—each time the lighting system in his room flashes, a new member of “the horde” (his collection of personalities) emerges. McAvoy shows his versatility in Kevin’s rapid shifts in voice, facial expression, and body language as he flips between nine-year-old Hedwig, prim and proper Ms. Patricia, an impassioned intellectual, and many others. Meanwhile, David wants to keep at bay and Glass wants to bring out Kevin’s most destructive personality: the Beast, who seeks to devour those who are impure and have not suffered.

Another character in this story is the Osaka Tower, a fictional Philadelphia skyscraper—now the world’s tallest—that the film repeatedly references. The tower, with its sustainable advancements and intriguing shape, symbolizes mankind’s ability to create engineering wonders. Perhaps that is a kind of superheroic feat.

As with his previous films, Shyamalan interjects metatextual statements regarding what’s happening in the film. In this case, it’s comic book storytelling techniques. Unfortunately, when Mr. Glass’s mother starts doing so, it seems completely out of character.

The film’s biggest fault is that it gets so caught up in delivering its message about human potential that the story goes on for too long. What could have been a profound statement about the societal obsession with superheroes morphs into a Hollywoodesque rainbows and butterflies ending.

There is much to like in Glass: twists, conflict, distinctive music, compelling backstory, and less ostentatious superhero outfits. Nevertheless, if a film like Glass hits the viewer over the head too hard with its message, its creator’s vision might end up shattered.–Douglas J. Ogurek ****

No comments:

Post a Comment