This excellent book is currently available as part of a Tachyon Humble Bundle, which includes several other books that went down very well here at TQF Towers, such as Pirate Utopia by Bruce Sterling, Yesterday's Kin by Nancy Kress and Slow Bullets by Alastair Reynolds.

Short stories don’t seem to have played a major part in Kate Elliott’s career. The twelve collected in The Very Best of Kate Elliott (Tachyon Publications pb, 384pp, $15.95) include all her published stories; none appeared in magazines; all are from anthologies or previously unpublished. She’s had twice that number of novels published, so it’s a fair bet that in truth her very best work lies there. And yet no reader would guess that from how good these stories all are. The book also includes four essays and an introduction, “The Landscape That Surrounds Us”, which sets out an explicit agenda.

Wednesday, 29 November 2017

Monday, 27 November 2017

Westworld, Season 1, by Jonathan Nolan, Lisa Joy and chums (HBO/Sky Atlantic) | review by Stephen Theaker

In the future life is too easy (good to know they fixed that whole global warming thing!) and so people jazz up their lives by coming to Westworld, a live action roleplay version of Red Dead Redemption, with robots playing the parts of all the non-player characters. The original film didn’t spend a great deal of time thinking about how any of this would work, simply showing people having a gunfight and bedding girls in brothels before setting Yul Brynner off on his famously terrifying rampage, but this new series is all about life in Westworld, and specifically what life is like for the robots who live there. For reasons best known to the park’s founders (one of whom is here played by Antony Hopkins, bringing his usual gravitas to a show that really appreciates it, since it is trying its hardest to be taken seriously), these robots, rather than being all run by some central computer system, have individual minds of their own, some of which have been operational for over thirty years, and they are beginning to have strange thoughts. They start to notice the glitches in their matrix, they start to remember their mistreatment at the hands of the park’s patrons, and they start to get angry about it. Thandie Newton, Evan Rachel Wood and James Marsden portray brilliantly some of the androids as they react to their dawning knowledge of their unconscionable situation, and here the show is at its best: how should we treat non-human people, and how will they react to that treatment, it asks. The programme’s problems come when you think too much about the park itself, and how it is supposed to work, and why people would want to go on holiday in such an unpleasant and horrible place. Yes, we’re happy to play Red Dead Redemption, but when you fall off your horse in that game you won’t break your actual neck. Westworld guns may not work when pointed at a human, but a knife will kill you just as quickly if a visitor decides to kill you and there aren’t any androids around to stop them. Would anyone want to go to dinner in a place where your fellow holidaymakers could start sexually assaulting someone right in front of you? And would the people who liked the idea of doing that kind of thing be happy to be filmed doing it? The programme does show one chap being blackmailed, so it’s unclear why this doesn’t bother everyone else. Equally odd is the way the quest lines work. They seem to proceed whether any players turn up or not, which leads to a great deal of damage being done to the scenery and the androids, all of which (it’s a major plot point) needs to be repaired, apparently pointlessly. Hard to understand why they don’t just use squibs for the explosions of blood, rather than wrecking the androids every day. And why use expensive androids rather than cheap human actors, as, for example, in Austenland? Plus, if you’re a guest who rolls out of bed a few hours late, how happy would you be to find that all the storylines have gone on without you? Would you be happy paying $40,000 a day to twiddle your thumbs? The important new storyline being created by Hopkins doesn’t seem to have any role for a human at all – though that might foretell a twist to come in season two, showing that the new storyline is not actually the one we’re shown; there do seem to be some metagames going on. (Though there’s nothing to suggest this in the first series, I wondered if it will eventually be revealed that the Earth faces disaster and so the park is an attempt to accelerate the evolution of post-humans who might survive it.) It’s an HBO programme, so there’s a requisite amount of nudity. Most of it is degrading and unsexy, in the course of the androids being repaired, reprogrammed and analysed; you’re supposed to feel bad for the androids, as demonstrated very clearly by a scene where Antony Hopkins’ character rips away the clothing a lab technician has allowed one robot, but you feel bad for the actors too. That doesn’t stop it being an interesting programme, though, and it rewarded the time it took to watch it with some later developments making clever sense of what had previously appeared to be storytelling non sequiturs. I would never go there on holiday – at least in Austenland the food looks nice! – but I’ll be happy to watch more idiots risk it. Here’s hoping for Roman World in season two. ***

Monday, 20 November 2017

iZombie, Season 2, by Rob Thomas and chums (The CW/Netflix) | review by Stephen Theaker

Liv Moore is a zombie, after being scratched by one at a really wild boat party a couple of minutes into season one. Luckily she won’t go “full Romero”, as they call it here, as long as she keeps snacking on brains. Since the brains work just as well if the owner is already dead, she got a job in a morgue, where she works with lovable Englishman Ravi Chakrabarti (Rahul Kohli), who soon learnt her secret and began to work on finding a cure. In season two Liv continues to use her brain-visions to solve murders with Clive Babineaux (Malcolm Goodwin), a grumpy detective. What she doesn’t know is that Vaughn Du Clark (Steven Weber), the owner of Max Rager, the energy drink involved in kicking off the original zombie freakout on the boat, is experimenting on zombies and has ensnared someone close to Liv… At nineteen episodes this series is perhaps a bit longer than it needs to be (season one was a tidy thirteen), and having a couple of arch-enemies in the main cast means that (like the second season of Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles) we check in with them very frequently, even though the meat of the programme isn’t the ongoing arc, it’s the stories of the week, where the humour of Liv dealing with her new brain-given personalities make it come close to being the replacement for Psych that I really, really want. This season includes episodes where she eats the brains of a fraternity brother, a real-world vigilante, a librarian who writes erotic fiction, and a country singer, always with amusing consequences. The funnier it is, the more I like it. ***

Thor: Ragnarok | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Slugfests, humour, otherworldly settings, eccentric characters. What more could you ask for?

Recent Star Wars and Transformers films are way too dramatic and way too serious. Think about it – a grand declaration to “fulfill … your … destiny” from a creature whose face looks like a pool of vomit? Conversely, films in the Avengers universe continue to have fun with their own ridiculousness. The visually spectacular comic action/adventure Thor: Ragnarok, directed by Taika Waititi, stays true to this strategy.

Recent Star Wars and Transformers films are way too dramatic and way too serious. Think about it – a grand declaration to “fulfill … your … destiny” from a creature whose face looks like a pool of vomit? Conversely, films in the Avengers universe continue to have fun with their own ridiculousness. The visually spectacular comic action/adventure Thor: Ragnarok, directed by Taika Waititi, stays true to this strategy.

Monday, 13 November 2017

The Expanse, Season 1, by Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby, Robin Veith and chums (Syfy/Netflix) | review by Stephen Theaker

James S.A. Corey’s novel Leviathan Wakes was one of the first books I ever requested from NetGalley, back in 2011, but I never got around to reading it. This excellent television version suggests that was a big mistake. As the series begins, humans have not yet left the solar system, so far as we know. There is a good deal of tension between Earth, Mars and those who live further out. Julie Mao, a young woman with connections to the Outer Planets Alliance, has gone missing, and a freighter is attacked while investigating what we know to be the ship she was on. Our protagonists are a group from the freighter who survive, led by James Holden and Naomi Nagata, trying to find out what happened and why, and a cop on Ceres, Joe Miller, played by Thomas Jane, who also has a very groovy haircut, and has been hired to investigate the young woman’s disappearance. It may not be a surprise to discover that there is a lot of shady stuff going on, but that’s not to say there aren’t plenty of surprises. This is a proper science fiction television series with a really good series-length plot that feels perfectly paced and still makes each episode feel like a significant chapter in the story. The effects are at times absolutely excellent, and never less than needed to tell the story clearly. The cast is excellent, and seem to be taking it all very seriously. I’m very much looking forward to season two. ****

This review originally appeared in Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #59, which also included stories by Rafe McGregor, Michael Wyndham Thomas, Jessy Randall, Charles Wilkinson, David Penn, Elaine Graham-Leigh and Chris Roper.

This review originally appeared in Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #59, which also included stories by Rafe McGregor, Michael Wyndham Thomas, Jessy Randall, Charles Wilkinson, David Penn, Elaine Graham-Leigh and Chris Roper.

Wednesday, 8 November 2017

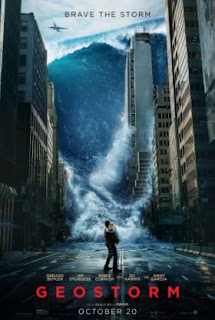

Geostorm | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Cliché-ridden? Yes. Stupid? Perhaps. Enjoyable? Undoubtedly.

Gerard Butler’s presence in a film may be, for some, a red flag. For me, it’s a draw – typically, Butler plays an aggressive type who doesn’t take crap from anyone. In Geostorm, he sticks to his calling card as tough guy American scientist Jake Lawson.

Gerard Butler’s presence in a film may be, for some, a red flag. For me, it’s a draw – typically, Butler plays an aggressive type who doesn’t take crap from anyone. In Geostorm, he sticks to his calling card as tough guy American scientist Jake Lawson.

Monday, 6 November 2017

Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Season 1, by Max Landis and friends (BBC America/Netflix) | review by Stephen Theaker

Elijah Wood plays a hotel busboy, Todd Brotzman, who discovers a bloodbath in a hotel room, just after apparently seeing himself (in pretty bad shape) in a corridor. He loses his job, but the universe seems to give him a new one, whether he wants it or not, as the assistant to Dirk Gently (Samuel Barnett – Renfield from Penny Dreadful, not I would ever have realised that without the help of the IMDB), a detective who doesn’t rely on evidence so much as the fundamental interconnectedness of all things. The story involves an equally holistic assassin, the Rowdy Three (all four of them), two police officers, the FBI, the CIA, and Todd’s sister, whose illness causes her to have hallucinations. Her brother’s recovery gives her hope, but all the nonsense that’s going on would be enough to make anyone doubt their grasp on reality. It’s a long time since I read the two novels, but this seems from a reference to a sofa and Thor to be loosely a sequel to them. The first Dirk Gently novel grew out of what was once the unused script for Shada, and here Dirk Gently is very explicitly Doctor Whoish. He’s a bit more useless and self-doubting than the Doctor, but you could put most of his dialogue in Tom Baker or David Tennant’s mouth without it sounding at all odd, or at least, without it sounding any odder. I thought this was brilliant, a total delight, an unfathomably successful cross between Who and Fargo (the series), with perhaps a dash of Psych. Every change of scene takes us to a great character. Fiona Dourif is particularly spectacular as Bart Curlish, the holistic assassin who believes that the universe sends her to the people that she needs to kill, but has never slept in a hotel room or used a shower. If her father Brad Dourif ever retires from being cinema’s favourite psychopath, there’s no need to worry: the family business is in good hands. Jade Eshete is also terrific as Farah Black, a private security operative who is trying to rescue her old boss’s daughter. If the show has any flaw at all, it’s that it has a slight case of what I call Hellboyitis (after the first film), where we seem to spend less time with the title character than with the chap who has just entered his world, but Elijah Wood is so likeable, even playing a bit of a jerk, that you can never resent the programme focusing on him. After the madness is over, just as the programme seems ready to settle into being Psych, it gets even better: the ending barges in and sets up season two very nicely. I would never have expected to be cheering just because someone was holding a rock, but that’s where this excellent show takes you. *****

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)