Wednesday, 30 November 2016

Star Trek: Gold Key Archives, Vol. 1, by Dick Wood, Alberto Giolitti and Nevio Zeccara (IDW Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

Back when the William Shatner version of Captain James Kirk first commanded the USS Enterprise, Gold Key published these cheesy but energetic stories about him and his crew; even in those early days for the franchise, half-Vulcan first officer Spock must have been the clear breakout character, since he appears more prominently than the captain on four of the six covers. Tony Isabella explains in the introduction that none of the creators involved in this series saw any episodes before starting work, which may explain why Scotty is in these issues an awkward blonde, and why in “The Planet of No Return” an encounter with a plant civilisation ends with the planet being scoured of all life, on Spock’s urgent recommendation. In “The Devil’s Isle of Space” the crew nonchalantly leaves convicts to be killed in an explosion, simply because it is “the way of their society”. These are big-scale stories where anything goes. In “Invasion of the City Builders”, a planet’s land has been almost completely covered by cities, thanks to automation gone too far, and “The Peril of Planet Quick Change” features missiles being fired into the planet’s core. In “The Ghost Planet” the ship drags the rings away from a planet, and in “When Planets Collide” the ship must somehow stop two worlds from crashing into each other, an impact which would pitch many of the planets of the Alpho galaxy “out of orbit… to burn in space!” Galaxies seem to be quite small here, and the ship seems to visit a new one every issue! Time is measured in lunar hours and galaxy seconds, everyone in the universe speaks Space Esperanto, and Kirk calls aliens “space scum”. So the stories are goofy, but that only makes them more enjoyable. It does capture that sense from the original series that the universe was an incredibly dangerous place where even heroes like Kirk and Spock would only survive if luck was on their side. The newly recoloured art looks great, and the simple six-panel grid layout makes for very easy reading. ***

Monday, 28 November 2016

A Slip Under the Microscope, by H.G. Wells (Penguin Classics) | review

The precise definition of science fiction has always been a matter for debate, the simplest answer being the stuff H.G. Wells wrote about. With books like The Time Machine (time travel), The First Men in the Moon (space travel), The War of the Worlds (alien invasion), The Shape of Things to Come (future history), The Invisible Man (experimentation on oneself) and The Island of Doctor Moreau (experimentation on others) he staked out the territory of a genre that still thrives, still finds new places to go, almost seventy years after his death. This fifty-five page Penguin Little Black Classic contains two of his short stories which don’t quite fit that narrative. The title story, “A Slip Under the Microscope” is science fiction of the other kind, a story about science, where a driven young student, labouring under the pressure of being a working class boy at the College of Science, where pupils on scholarships are not even invited to sit down when meeting their tutors, makes a terrible mistake during an examination. The other story, “The Door in the Wall”, is more fantastical, about a government minister who longs for the secret garden he found as a child, the magical entrance to which only ever presents itself again when he has not the time to enter it. Both stories are very, very good. The first couple of Little Black Classics I read – As Kingfishers Catch Fire by Gerard Manley Hopkins and Aphorisms on Love and Hate by Friedrich Nietzsche – were dreadful, but it’s clear I judged the series too soon. Stephen Theaker ****

Ten free ebooks from the paperback library!

- Five Forgotten Stories, John Hall

- His Nerves Extruded, Stephen Theaker

- Pilgrims at the White Horizon, Michael Wyndham Thomas

- Professor Challenger in Space, Stephen Theaker

- Quiet, the Tin Can Brains Are Hunting! Stephen Theaker

- Space University Trent: Hyperparasite, Walt Brunston

- The Day the Moon Wept Blood, Stephen Theaker

- The Doom That Came to Sea Base Delta, Stephen Theaker

- The Fear Man, Stephen Theaker

- The Mercury Annual, Michael Wyndham Thomas

Snap them up!

Saturday, 26 November 2016

Journey into Space: Frozen in Time, by Charles Chilton (BBC Audio/Audible) | review

This fifty-seven minute adventure is the fifth Journey into Space. The first three, Operation Luna, The Red Planet and The World in Peril, were long, episodic sagas broadcast in the fifties, while the last three, The Return from Mars, Frozen in Time and The Host were radio plays broadcast in 1981, 2008 and 2009 respectively. All were written by Charles Chilton, except The Host. As this story begins the usual crew of Captain “Jet” Morgan, “Doc” Matthews, Mitch and Lemmy are on their way back from Neptune in the Ares. The cast is all new except David Jacobs, who played several supporting characters in the original trilogy, often in the same scene, and here plays Jet Morgan. A problem with his cryogenic sleep unit meant Jet has been awake for practically the whole thirty-year trip home, and a good thing too or the ship might well have been destroyed. He wakes the others as they approach Mars, long-forgotten and short on fuel. They land near the Saviour 1, itself stuck there after developing a fault. Good thing Mitch is here, since in this distant future of 2013 it’s unusual for a crew to include an actual engineer. The media rep and the health and safety officer aren’t much good at fixing spaceships. The captain is now a “flight manager”, and Doc notes with bemusement how the remaining crew of the Saviour 1 spend all their spare time playing games on their screens. (If Charles Chilton could see us now!) They seem unwell, and there are clues to suggest that they’ve been up to no good... This story keeps the mood of the originals very well, remarkably so given the fifty years that had passed when this was produced, and that’s helped by the use once again of Doc’s diary entries to bridge narrative gaps. The crew all behave in recognisable ways, even down to the flashes of the old irritation with each other at times of stress. It’s just a shame that it stops after one hour, instead of ten. Stephen Theaker ****

Wednesday, 23 November 2016

Star Trek, Vol. 1, by Mike Johnson, Stephen Molnar and Joe Phillips (IDW Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

The ongoing Star Trek comic follows the adventures of the Chris Pine version of Captain James Kirk and his crew, as shown in Star Trek XI, XII and XIII. This first volume collects issues one to four, set soon after the eleventh film, with Kirk in charge of the USS Enterprise a good deal sooner than in the previous continuity, and the five year mission off to an early start. Oddly, though, they still run into many of the same situations, since the two stories here are adapted from the television episodes “Where No Man Has Gone Before”, in which crewman Gary Seven acquires the powers of a god after the Enterprise tries to cross the galaxy’s edge , and “The Galileo Seven”, in which a shuttlecraft crew led by an as-yet untrusted Spock is lost and stranded on a dangerous world with aggressive locals. James Blish’s prose adaptations tended to improve on the original programme, so maybe these comics could do the same? Sadly not. Adapting forty-minute episodes to forty-page comics doesn’t leave room for a lot of detail, and although the stories are subtly changed by taking place in the new continuity they feel sketchy and underfed. The artwork is good, the likenesses pretty decent, it’s just that the project itself feels a bit pointless. Perhaps it’s aimed at fans of the new films who haven’t watched the original show? Either way, it’s good to see that subsequent volumes add new, original stories to the mix. **

Monday, 21 November 2016

Wailing Ghosts, by Pu Songling (Penguin Classics) | review

Translated by John Minford, these are fourteen very short fantasy stories and tall tales, written by a Chinese author who lived from 1640 to 1715. They are set in a world of fox spirits, demons and red-headed monsters. The book doesn’t explain its humanoid foxes, but they seem to be like those in The Heavenly Fox by Richard Parks, where foxes who lived to the age of fifty could assume human form, and those who lived to a thousand became immortal. Because the stories are so short, it’s difficult to say much about them without giving away the entire plot, but the highlights include “King of the Nine Mountains”, about a man who rents his back garden out to a party of a thousand fox spirits and promptly betrays them, and “Butterfly”, where a syphilitic horny teenager, Luo Zifu, “breaks out in suppurating sores, which left stains on the bedding” and is thus driven out, eventually to find happiness with Butterfly, a supernatural lady who lives in a grotto. He blows it, of course. Other stories include “The Monster in the Buckwheat”, “Scorched Moth the Taoist”, “The Giant Turtle” and “A Fatal Joke”, which is barely a page long but features the book’s most horrible image. When a book this good costs 80p, you’d be daft not to buy it. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday, 18 November 2016

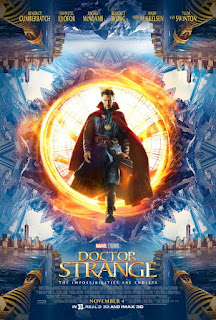

Doctor Strange | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Top-notch acting meets special effects in world-hopping tale of narcissist’s downfall and rebirth.

Full disclosure: I am not a comic book nerd, and I knew nothing about Doctor Strange before seeing the latest Marvel blockbuster that bears his name. I am, however, quite familiar with the acting talents of Benedict Cumberbatch, Tilda Swinton, and Chiwetel Ejiofor. So it was with great enthusiasm that I anticipated this superhero origin film. The wait paid off.

Full disclosure: I am not a comic book nerd, and I knew nothing about Doctor Strange before seeing the latest Marvel blockbuster that bears his name. I am, however, quite familiar with the acting talents of Benedict Cumberbatch, Tilda Swinton, and Chiwetel Ejiofor. So it was with great enthusiasm that I anticipated this superhero origin film. The wait paid off.

Wednesday, 16 November 2016

The Last Weekend, by Nick Mamatas (PS Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

Even before the collapse, Vasilis Kostopolos was not a nice guy, and not a happy guy either. A self-loathing alcoholic who follows an ex-girlfriend to Boston, who follows random women on the subway while abusing them in his mind, who doesn’t mind if the money he spends on drink helps fund the IRA, he ends up in San Francisco, a surprisingly good place to be when the dead start to rise. There are no cemeteries there, and the zombies struggle with the big hills. He’s a writer, and he can prove that with the print-out of his one published story that he keeps in his pocket at all times, but he takes a job as a driller. When the dying seem likely to turn, he gets a call. If he’s lucky, he gets there once they’re dead but before they’ve revived, but he’s rarely lucky. Turns out he’s pretty good at the job, or at least he doesn’t quit or get eaten. He’s a guy who spent his “adult life trying to avoid adult life, living a simplified version of it without dreams of a family”. Before the collapse he would consider killing himself “a dozen times a day, maybe more”. So when everything falls apart for everyone else (at least in the USA; nowhere else seems to be affected) he copes pretty well, his life hasn’t got much worse. (Also a theme of the later show Fear the Walking Dead, where a junkie adapts better to the apocalypse than the rest of his family.) He even starts to meet women: Alexa, who shoots a boy who jumps out at them, pretending to be a zombie; Thunder, a friend of the dead boy who shamelessly steals Vasilis’s stuff; Jaffe, a civil servant who kept on serving after the collapse. Thunder and Alexa share a desire to get to the bottom of things, to uncover the mysteries of the apocalypse, to find out what the government (such as it is) is hiding, and Vassily gets mixed up in their plans despite himself. This is a terrific book, the kind of thing you might expect if McSweeney’s had a horror imprint, intelligent, provoking, self-aware, and full of interesting ideas. You wouldn’t ever want to be this guy, as a writer, or as a human being, but you can understand why he survives, and why it takes the breakdown of human society for him to write his great American novel. ****

Monday, 14 November 2016

Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange, translated by Malcolm C. Lyons (Penguin Classics)

This is a collection of medieval Arabian fantasy, or at least half of it, the other half being lost to the sands of time. Malcolm C. Lyons provides a new translation, rendering the book rather more readable than the excellent and informative (but spoiler-heavy – read it after the rest of the book) introduction by Robert Irwin suggests the original to be. On Goodreads a potential reader has asked whether the book is suitable for children, and the answer is most definitely no. Grimdark a thousand years before George R.R. Martin or Joe Abercrombie, this is brutal, horrible and cruel, stories of terrible people doing awful things in a world ruled by capricious and sentimental tyrants. Racists, rapists and murderers, these characters lie, cheat and steal their way to happy endings, often saved by a last-minute religious conversion or appeal to a deity. That the stories are about such awful people wouldn’t be so jarring if it weren’t for the religiosity of it all. Irwin cautions against “the enormous condescension of posterity”, quoting E.P. Thompson, and that’s a fair point, but it’s hard to really enjoy stories in which slavery and sexual aggression are so positively portrayed. For example, in “The Story of Sakhr and Al-Khansa’ and of Miqdam and Haifa’”, Sakhr sneaks into a girl’s tent and draws his sword, saying “if you utter a word I shall make you into a lesson to be talked of amongst all peoples breaking your joints and your bones”. The girl “saw that he was handsome as well as eloquent; she weakened and looked down bashfully as he got into bed with her”. That’s fairly typical, and that story gets worse. The book is also quite repetitive, with everyone who is half-decent to look at being described as like the moon, Indian swords all over the place, people hitting themselves in the face all the time, and every man being “delighted” to discover that his copulative partners are still virgins. (In one case, that’s even though they slept together earlier in the story.) That’s not to say there’s nothing to enjoy here. Though women are generally shown in a terrible light and treated horribly – for example, a king is told the story of ‘Arus al-’Ara’is to make him glad his daughter died! – several are shown to live independently and drink wine very happily. It was surprising to see an acknowledgment of the existence of gays and lesbians, even if it was to discourage such romances, and in the story of the Foundling and Harun al-Rashid there are heavy hints of male romance. “No one is going to rub him down except me,” says the executioner Masrur in a bath-house. The story of Miqdad and Mayasa shows the former killing enemies like a supercharged Conan the Barbarian and the desert being rolled up for the latter. In the story of Julnar of the Sea a king says of a gorgeous woman, “Praise be to God, Who created you from a vile drop in a secure place!” A nice way of putting it. The story of Abu Disa is amusing: a browbeaten weaver is pushed into posing as an astrologer, and through various turns of fortune makes a series of astonishing and lucrative predictions. The story of Sa’id Son of Hatim al-Bahili is a fascinatingly curious attempt to retcon the Bible. Overall, though, I found the book such a struggle to get through that I wouldn’t recommend it on its own merits as a collection of stories; they’re just not very good; but as a curiosity, as a glimpse into the storytelling of the past, as a translation and as a historical artefact it may find appreciative readers. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday, 9 November 2016

The Zombies That Ate the World, Vol. 1: An Unbearable Smell! by Jerry Frissen and Guy Davis (Humanoids) | review by Stephen Theaker

This digital album tells four of the “everyday occurrences that happen in the twilight of Los Angeles”, to quote the line that ends them all. It is 2064 and the dead have been coming back to life. They aren’t violent, at least no more than they were when they were alive, and so the government has decreed that the living and the dead must live peacefully together. That’s going pretty well until Otto Maddox, a filthy rich man with extremely expensive hobbies, has an actor disinterred, Franza Kozik. When alive, she starred in such films as Queen of the Zombies and Flesh Feast, and once out of her coffin she picks up where she left off, eating brains, but for real this time, and that inspires other zombies to try it too. The other stories here include a historian of the twentieth century who wants his reanimated father-in-law peacefully disposed of, and a Nazi type who wants the brain of a particular zombie rewired to restore its intelligence. All four stories feature, to a greater or lesser extent, Karl Heard, who with his sister Maggie and their hulking associate The Belgian, makes a barely legal living as a zombie catcher. Elsewhere, Christians are executing thousands of people in the Holy Land in hopes of persuading Jesus to return, and a scientist has reanimated a dinosaur. This is an odd book, with a humorous tone that sits a bit uneasily with the tawdry and horrible stories it is telling, but it is worth reading, especially for the art of Guy Davis, who readers might know from Sandman Mystery Theatre or The Marquis. His style of drawing is exceptionally well-suited to the portrayal of the rotting undead, not to mention the other sleazy types in the book. ***

Monday, 7 November 2016

Ouija: Origin of Evil | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Will this prequel overcome its predecessor’s mediocrity? Yes.

This Halloween season, horror film fans had slim pickings at the theatre. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, like me, they felt disappointed when they learned about the season’s feature offering: Ouija: Origin of Evil.

This Halloween season, horror film fans had slim pickings at the theatre. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, like me, they felt disappointed when they learned about the season’s feature offering: Ouija: Origin of Evil.

Arrow, Season 2, by Marc Guggenheim and many others (Warner Bros Television) | review

Oliver Queen was a sleazy rich kid who took his girlfriend’s sister away on a disastrous yacht trip, leaving him marooned on an island, from which he was rescued five years later. He returned with a new set of skills, and a new sense of purpose, determined to use his archery and acrobatics to take down the wealthy one percenters who have been bleeding the city dry. Unfortunately, the first season of Arrow was in its early stretches often indistinguishable from stablemate Gossip Girl, but as its roster of costumed characters built up it improved, an episode with the Huntress attacking her father’s compound being particularly good, and it ended well, with a serious threat that pushed the fledgling hero to his limits. Season two is even better, putting Oliver and his night-time nom de guerre under an ever-tightening screw, as a friend from the past returns with a grudge. Flashbacks to the island continue, moving more or less in pace with current-day events, creating an unusual effect whereby the viewer must constantly rethink the Oliver we met in the programme’s first episode. DC fans will appreciate the introduction of a certain group of villains sent on deadly missions by (the remarkably slim) Amanda Waller, and by the end Black Canary is in it so much they could have put her name in the titles. Supporting characters Diggle and Felicity are also given plenty to do, though Oliver’s family and friends, especially his mother and Laurel, tend to zig and zag rather randomly whenever the plot requires it. The season draws on classic New Teen Titans, and from there brings us one of the best villains yet in a television superhero series. Despite Felicity’s best efforts, there isn’t much humour, and the dialogue is rarely more than functional; the thrilling story just about makes up for it, but one hopes John B. Arrowman plays a bigger part in seasons to come. In his few scenes here he displays a totally welcome cheekiness that was rather buried in season one. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday, 2 November 2016

Marshals, Book 1: Darkness and Light, by Dennis-Pierre Filippi and Jean-Florian Tello (Humanoids) | review by Stephen Theaker

Hisaya is a marshal on the planet Iriu, working in an area under the control of the air consortium. Her robot partner is wrecked during the apprehension of a former robo-trafficker, but her grandad can’t supply her with a replacement this time: he’s switched to making buxom humanoid pleasure bots (though they can fight when needed, and it will be needed). Instead he introduces her to Tetsu, a young mechanic with a passion for robotics who has built a nifty new defence bot – and she can have it if she will take Tetsu on as an apprentice. A five-page naked sauna scene with the pleasure bots later, and Marshal Hisaya returns to the city with her new apprentice and her new bot, just in time for a series of treacherous attacks that will leave everyone running for their lives. Darkness and Light is the first of four digital albums, also collected in a single hardcover book from the same publisher. It does a good job of setting up this steampunky, Final Fantasyesque world, and Marshal Hisaya is quite the badass. The nude scenes feel a bit redundant and pandering, and it isn’t always easy to follow the action, but in general the art is very appealing and characterful, a bit reminiscent of Ian Gibson’s 200AD work, with the extra detail that working on an album rather than weekly pages can allow. The colours, by Studio Bad@ss, do a great job of picking out all that detail and letting the eye make sense of it all. A good start to the series. ***

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)