Monday, 27 February 2017

Savage Dragon Archives, Volume One, by Erik Larsen (Image Comics) | review by Stephen Theaker

This huge black and white collection includes issues one to three of the original Savage Dragon mini-series, plus the first twenty-one issues of the ongoing series, all of it written and drawn by the character’s creator, Erik Larsen. As with the Walking Dead books, there is nothing to indicate where one issue begins and the next ends, making for an intense helter-skelter of a reading experience, fights with full-page villains constantly bursting out of nowhere. There are moments of peace here and there, but the Dragon’s life is not one of quiet contemplation. He was found in a vacant burning lot, his skin green and tough, his head sporting a fin, and his arms as thick as tree-trunks. He remembers nothing about his life, but remembers baseball and the president. A desperate friend, Frank, finds a way to finagle the Dragon into joining the police force (in a way that he’ll come to greatly regret), and thus begins the jolly green giant’s career as the official strong arm of the law. It’s tremendously exciting, bonkers, and inventive, one bizarre battle following another, with very little time wasted on introducing the villains – they just get on with it – and the ongoing storylines and mysteries are always ticking away nicely. The artwork to me seems quite similar to John Byrne’s (ironically, since he comes in for some stick in the book as Johnny Redbeard), with the drama of Frank Miller, and the crackling kinetic energy of Jack Kirby. Reading it in colour might have helped me to make visual sense of some fight scenes quicker, but it still looked really nice in black and white. It reminded me of what I like so much about Invincible, a much later hit from the same publisher, in that it feels like a whole superhero universe in one book – even the guest appearances from Spawn and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are made to feel like an organic part of the over-the-top storytelling. Is it truly good? Hard to judge, because it’s playing by its own mad logic, but it’s certainly an enjoyable and unique experience. The subsequent five volumes were, on the whole, just as enjoyable. ****

Last chance to vote in the Theaker's Quarterly Awards 2017!

Voting is open to everyone, and you can vote for as many items in each category as you want.

At this stage only two things are guaranteed: Howard Watts is going to win best TQF cover art (but for which issue?) and Disasterpeace is going to win best music. Everything else is up for grabs!

Ties will be decided by the star ratings items received from our reviewers (where relevant), and if that doesn't do it, we'll ask Alexa to roll an appropriate dice.

The prestigious awards themselves can be seen to the right, but don't worry, whether you win or lose, you still rule.

Click here to vote!

Friday, 24 February 2017

Autumn Snow 1: The Pit of Darkness, by Martin Charbonneau, Joe Dever and Gary Chalk (Megara Entertainment) | review by Rafe McGregor

Stephen Theaker has been kind enough to allow me to indulge my nostalgia for 1980s fantasy gamebooks in his magazine and over the course of three reviews – The Voyage of the Moonstone (TQF55), The Buccaneers of Shadaki, and The Storms of Chai (both TQF57) – I’ve charted the remarkable story of Joe Dever’s Lone Wolf series. The latest of my reports contains a couple of surprises of the kind I’ve come to expect by now, given the series’ incredibly complicated publishing history, characterised by first falling victim to and then being perpetuated by the domination of internet technology at the turn of the century. To begin at the beginning, I first found out about The Pit of Darkness courtesy of Project Aon (www.projectaon.org), the voluntary organisation that has done so much to keep the series alive during its many years in the publishing wilderness, in a bulletin listing the current availability of Lone Wolf products dated 8 July 2016. Megara Entertainment founder Mikaël Louys began crowdfunding for the volume in September 2014, the main purpose of which was to secure the services of the original Lone Wolf illustrator, Gary Chalk, who had an apparently acrimonious split with Dever between the release of Castle Death (#7, 1986) and The Jungle of Horrors (#8, 1987). The gamebook is only available from the Megara website direct (www.megara-entertainment.com) and has been released in both French and English versions. The two are presented distinctly on the website and although the price is quite steep (about £30 at the time of my purchase, no doubt more now), it includes postage and packaging and my copy arrived promptly and in perfect condition. I nonetheless have two small complaints about Megara. First, they don’t seem to advertise very well – I ordered immediately after following the link from Project Aon and the copy I received is already a “THIRD PRINTING, REVISED” – what happened to the first two printings? Second, and this may well be the reason for being in a third printing already (assuming all three were released in 2016), there are quite a few typos and formatting errors in the book (albeit all minor).

Monday, 20 February 2017

Aldebaran, tome 1: La Catastrophe, by Leo (Dargaud) | review

Contact with Earth was lost over a hundred years ago, soon after it was hit by an economic crisis, though life isn’t too bad on the planet known as Aldebaran. A religious order rules, but their influence is barely felt in Kim’s little village on the coast, where the beach is endless and the ocean the sweetest blue. She dreams of getting back in touch with Earth. Marc, a boy who fancies her big sister, works as a fisherman; his dream is to go to the big city. The fishermen find some odd corpses in the water, monsters driven up from the seabed, and a stranger arrives with dire warnings of a disaster to come. No one believes him and he leaves, before a journalist turns up, hot on his trail – Marc takes her after him, and they begin to see some really weird stuff. And maybe it’s a good thing he isn’t at the village right now… This is the first of five French albums collected in Aldebaran: L’Integrale, recently reprinted. It’s a gorgeous book, inside and out, and it feels like this first volume barely skims the surface of this strange and beautiful world. Leo’s artwork is rather like a slightly stiffer Steve Dillon, his creatures as weird as Miyazaki’s. An English translation is available, but it’s possible to order the French version through UK Amazon too, if you fancy dusting off your GCSE French. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday, 17 February 2017

Now out: Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #58: Unsplatterpunk!

free pdf | free epub | free mobi | print UK | print US | Kindle UK | Kindle US

Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction #58: Unsplatterpunk! is now out! Guest-edited by Douglas J. Ogurek, this is a special issue, an anthology featuring five founding tales of unsplatterpunk, a brand new genre! Douglas describes it as “extreme horror stories [that] offer a positive message, whether blatant or subtle, within their otherwise vile contents”. So don’t expect any slap-up dinners in this issue!

As Douglas says in his editorial, this isn’t a volume you’d want to pull out on family reading night, and you might want to avoid discussing it in detail with your coworkers. But it is interesting! Here’s what Douglas had to say about the stories in this issue:

In M.S. Swift’s deliberately disjointed “A Desert of Shadow and Bone”, brutality meets philosophy in an extravaganza of limb hacking, gentry slaughtering, and drug use that makes a statement about corporate greed and the repression of women. What starts as an extreme, albeit intimate ritual beside a tree-lined natural pool builds to a climax that is both apocalyptic and indicative of personal growth.

There’s something awry about an impending birth in “Quand les queues s’allongèrent”. When you discover what it is, you’ll get a jolt of humour and revulsion. Antonella Coriander offers a slashing take on misogyny and women’s empowerment.

Drew Tapley’s “The Fisherman’s Ring” delves into the absurd as he unveils what really happens in the secretive ceremony to select the next Pope. You get ringside seats for a series of trials full of pain-tertainment. You also get hope and solidarity.

In “The Armageddon Coat”, the collection’s longest work, Howard Watts (who also supplies the terrifying cover) takes us on a more serious journey of two pre-teens as they try to make sense of their world following an alien attack. The theme of innocence vs experience swirls amid political maneuvering, mass destruction, and vicious fighting to survive.

We also have a handful of reviews this issue, from Douglas himself, Rafe McGregor and Rose M. Rye (yes – after two long years we have once again published a female writer!), and they look at the work of Martin Charbonneau, Joe Dever, Gary Chalk, Neil Gaiman and Daniel Egnéus, as well as the films Arrival and Doctor Strange, and season eleven of the television show Supernatural. The issue concludes with twenty-four pages of notes and ratings for almost everything Stephen Theaker read during 2016 but didn’t review for us.

Here are the munificent contributors to this issue:

Douglas J. Ogurek’s fiction, though banned on Mars, appears in over 40 Earth publications. He is the guest editor of this special issue. Ogurek founded the literary subgenre known as unsplatterpunk, which uses splatterpunk conventions (e.g. extreme violence, gore, taboo subject matter) to deliver a positive message. More at http://www.douglasjogurek.weebly.com.

Drew Tapley is a copywriter and journalist, and has been publishing in Canada, Australia, and his native England for the last decade, both in print magazines and journals, as well as online. He is now based in Toronto, and has been making short films for the last five years. Some of his films have screened at film festivals throughout the world. He was recently published in the UK’s Popshot Magazine, and has two published books: one fiction, and one nonfiction.

Howard Watts is a writer, artist and composer living in Seaford. He provides the wraparound cover art for this issue, as well as a brilliant story. His artwork can be seen in its native resolution on his DeviantArt page: http://hswatts.deviantart.com. His novel The Master of Clouds is available on Kindle.

M.S. Swift writes horror and dark fantasy inspired by the ancient landscapes of the U.K. His contemporary horror tales have been published by Ghostwoods Books, the First United Church of Cthulhu, Schlock! Webzine and Schlock! Bi-monthly. He is currently working on a dark fantasy series inspired by the late medieval witch hunts, the first story of which has been published through Horrified Press. His long-term goal is to write a series of weird tales inspired by the early work of Wordsworth and Coleridge. He is paying off the accumulation of negative karma by working in the English education system.

Rafe McGregor Rafe McGregor is the author of The Value of Literature, The Architect of Murder, six collections of short fiction, and one hundred and fifty magazine articles, journal papers, and review essays. He lectures at the University of York and can be found online at @rafemcgregor.

Rose M. Rye is an actual woman, honestly, but she’s writing for us under a pseudonym because she doesn’t really want to be hassled at work by people who disagree with her opinions about television.

Stephen Theaker’s reviews, interviews and articles have appeared in Interzone, Black Static, Prism and the BFS Journal, as well as clogging up our pages. He shares his home with three slightly smaller Theakers and works in legal and medical publishing.

As ever, all back issues of Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction are available for free download.

Monday, 13 February 2017

Fall of Cthulhu Omnibus, by Michael Alan Nelson, Mateus Santolouco and chums (Boom! Studios) | review by Stephen Theaker

This huge book collects six trade paperbacks in one epic volume. The first five stories, from “The Fugue” through to “Apocalypse”, concern the plans of Nyarlathotep, the creeping chaos, who has taken human form and resurrected Abdul Alhazred to write a new chapter of the Necronomicon, a chapter concerning the fate of Cthulhu, who sleeps undying under the waves in R’lyeh. A saga that ends with gods clashing and the Dreamlands spilling their nightmares upon the earth begins in a more mundane setting, with Cy and his girlfriend Jordan at a cafe, where Cy’s uncle, Professor Walt McKinley of Miskatonic University, shows up, rambling about the blood on his hands before taking his own life, right there, al fresco. He leaves Cy a big bundle of mysteries and a knife ornamented with eyes that follow you around the room. It’s the start of a story that will take Cy to the traditional Lovecraftian edge of madness and a long way beyond. He will meet allies, like Sheriff Raymond Dirk, whose family have long tried to keep the craziness in Arkham from bubbling malevolently to the surface, and Luci Jenifer Inacio das Neves, or Lucifer for short, a teenage rascal with a pretty decent handle on what is going on. The three of them will encounter nightmares and gods, monsters of all kinds, most startlingly of all the Harlot, who summons unhappy men to the Dreamlands and gives them what they want, for a horrible price. A variety of artists take turns to portray this amazing colossal woman as we pass through the book’s six hundred pages, and each captures her horror in a differently spectacular way. The sixth section of the book is in part an ironic epilogue, but mostly a prequel, showing what went down (if you’ll forgive me) in Atlantis long ago. Overall, this is a good solid attempt at a Cthulhu mythos comic book, very much in the style of what you might expect from an official TV adaptation of Lovecraft’s work, rather than the glancing references and nods we so often get. The scenes in the Dreamlands are the high points, different artists and art styles used to render their strangeness. Cthulhu’s name is in the title, but this is about the Harlot and Nyarlathotep and the humans caught in the middle of their battle. You wouldn’t want to be in their shoes when R’lyeh starts to rise… ****

Wednesday, 8 February 2017

Douglas J. Ogurek’s top five mass market sci-fi/fantasy/horror films of 2016

The fascination with superhero movies grows: half of the top ten grossing (U.S.) films of 2016 involved crusaders of one kind or another. Overall, last year’s SF/F/H film output brought some disappointments (e.g., Independence Day: Resurgence, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Suicide Squad (excepting the Joker and Harley Quinn)) and some silly yet fun fantasies (e.g. Gods of Egypt, The Huntsman: Winter’s War), as well as some pleasant surprises (e.g. Ouija: Origin of Evil). Though advertisements championed The Witch as the next super-scary horror offering (and critics seemed to agree), the film doesn’t hold a candle next to the last two decades’ masterpieces (i.e. The Blair Witch Project, The Ring, Paranormal Activity). So we horror fans patiently await the next attempt.

With the exception of Arrival, SF/F/H films are absent among major categories in this year’s Oscar nominations. Typical. But… Suicide Squad was nominated, for Best Makeup and Hairstyling. That’s the Joker and Harley Quinn again.

So here you go: my picks for the best SF/F/H films of 2016:

#5: Don’t Breathe – Suspenseful and fast-moving. The victim, a muscular blind veteran, becomes the aggressor when three unwitting thieves break into his home for what they think will be an easy job. There’s something quite unsettling about the thieves’ would-be killer standing feet away and using his enhanced non-visual senses like a predatory animal. Full review.

#4: Dr. Strange – This superhero origin tale details neurosurgeon Dr. Stephen Strange’s transformation from self-absorption to pursuit of a greater purpose. Great acting, strong visual effects (nominated for an Oscar in this category), and quite a bit of humour. Full review.

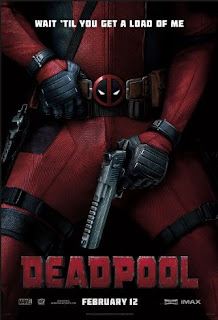

#3: Deadpool – Entertainment personified. You probably don’t want this superhero on your child’s lunchbox. The wise-cracking Deadpool breaks the fourth wall (i.e. he talks to the viewer), carries a Hello Kitty backpack, gets to his destinations via taxi, and never shuts up . . . and you don’t want him to. Fun (and funny) from start to finish. Like Ferris Bueller, with explosions. Full review.

#2: Arrival – This sci-fi drama does away with the explosions and the ridiculous dialogue of the typical alien invasion film. Instead, it’s a sophisticated exploration of language, perception of time, and human response to the unknown. Full review.

#1: 10 Cloverfield Lane – A play, a horror film, and a sci-fi mystery all rolled into one captivating package. So many great elements, the best of which is John Goodman’s portrayal of Howard. Are his intents in imprisoning the protagonist in his bunker malicious or altruistic? Even the kitchen table scene will have you completely absorbed. Full review.

There you have it: a blind killer, a jerk, a bigmouth, cryptic aliens, and an ineffable antagonist. Let’s see what 2017 brings. – Douglas J. Ogurek

See Douglas’s top five picks from 2015.

Monday, 6 February 2017

Travel Light, by Naomi Mitchison (Small Beer Press) | review by Stephen Theaker

Little baby Halla has the misfortune to be a fairy tale princess, of the sort whose mother has passed away and father has remarried. The new queen wants her killed, but luckily the baby’s nurse Matulli is from Finmark, and has the unusual knack of being able to turn herself into a bear. This she does, and carries the baby away into “the deep dark woods where the rest of the bears were waking up from their winter sleep”. She lives with the bear cubs, learning to appreciate the taste of crunched mice, and the way the forest speaks in smells to the bears. She spends much of her later youth living with a friendly dragon, and comes to see the world from a dragon’s point of view, where maidens are thoughtfully offered for dinner, and heroes interfere with everyone’s best interests, and kings squander the gold that dragons sensibly gather together. When her stay with the dragon comes to an end, her voyage begins, taking her all the way to Constantinople to meet the Emperor. The book gets a little drier here, less whimsical, more political, and this, plus a certain amount of threatened and implied sexual violence, may explain why it did not become the famous children’s classic posited in the introduction. The way it approaches the hypocrisy of the established church is well done, but maybe not where readers might have hoped it would go after starting off with bears and dragons and a valkyrie. But it is still a very good book, one that plays clever games with defamiliarization, perception and time, and it lets its princess heroine decide for herself, a half century before Frozen and Princeless, whether her particular destiny was to marry or not. ****

Friday, 3 February 2017

Closing to fiction submissions till April (except from female writers)

We have enough stories in hand for issue 59 now, so we are closing to fiction submissions until April 1, when we will re-open to subs for issue 60.

However, because all the stories accepted so far for issue 59 are by chaps, we'll remain open to fiction submissions from female writers (as well as new episodes in our ongoing serials).

Guidelines here.

However, because all the stories accepted so far for issue 59 are by chaps, we'll remain open to fiction submissions from female writers (as well as new episodes in our ongoing serials).

Guidelines here.

Wednesday, 1 February 2017

Split | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Shyamalan triumphs again in exploration of mind-body connection and victim empowerment.

By now, it’s pretty much a sure thing. When I go to an M. Night Shyamalan film, I’m going to enjoy it. I’m going to get odd characters, interesting ideas, an intriguing setting, surprises, and a doozy of a climax, as well as a deeper meaning to reflect upon for years to come.

By now, it’s pretty much a sure thing. When I go to an M. Night Shyamalan film, I’m going to enjoy it. I’m going to get odd characters, interesting ideas, an intriguing setting, surprises, and a doozy of a climax, as well as a deeper meaning to reflect upon for years to come.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)