Weird Bond.

Like Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Ian Fleming seemed to tire of his literary creation quickly. After three novels presented almost exclusively from James Bond’s point of view, he is absent from the first chapter of the fourth, the first ten chapters of the fifth, and the latter – From Russia, with Love (1957) – ends with him dying at the hands (or, rather, the foot) of Colonel Klebb of the Soviet Union’s SMERSH. Bond was resurrected in Dr No (1958), but there were a series of departures and experimentations after Goldfinger (1959): For Your Eyes Only (1960) is a collection of five short stories; Thunderball (1961) is Fleming’s novelisation of a screenplay, which he wrote with four collaborators; The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) is written in the first person, from the point of view of a Canadian woman, with Bond appearing only in the final third; On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963) ends with Bond being married and immediately widowed; and You Only Live Twice (1964) ends with Bond en route to the Soviet Union where – we imagine – imprisonment, torture and death await. The remaining two books were published after Fleming’s death. Bond was resurrected for the second time in The Man with the Golden Gun (1965), but Fleming had completed only a first draft by the time of his death and the novel is slim and unsatisfying. Octopussy and The Living Daylights (1966) is a collection of four short stories, two of which are very short indeed. I cannot recommend any of the fourteen books because although Fleming was a master storyteller whose clean, crisp prose is reminiscent of Hemingway, the narratives all betray implicit and explicit racism and homophobia and a misogyny that borders on sexual sadism. I mention them, however, because of the “SPECTRE Trilogy”, which comprises Thunderball, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, and You Only Live Twice. The trilogy provides the most comprehensive portrayal of Bond’s private life, fleshing out his personality beyond his profession as an authorised assassin. It also stretches the espionage thriller genre to its very limits, spilling over into speculative fiction.

Tuesday 28 August 2018

Closet Dreams, by Lisa Tuttle (infinity plus) | review by Stephen Theaker

Part of the infinity plus singles series, which aim to bring back the feel of buying a vinyl 45, and then liking it so much you would buy the album too. Short stories are the singles, collections the albums. In this case the single has already been a hit, having appeared in Postscripts, been shortlisted for a Bram Stoker Award, and and won the International Horror Guild Award. It’s the chilling story told by a young woman, who says, “Something terrible happened to me when I was a little girl.” Held captive in a small closet by an abductor, she describes the miraculous escape that baffled her family and the police. It’s not a long story, so it’s hard to say much more without giving too much away, but it certainly achieved the goal of making me want to read more by the same author. ****

Sunday 26 August 2018

The Penny Dreadfuls, Volume 2, by David Reed and Humphey Ker (BBC Audio) | review by Stephen Theaker

The Penny Dreadfuls are a comedy troupe – Humphrey Ker, David Reed and Thom Tuck – three chaps who retell classic tales in comedic fashion. The stories are scripted, rather than improvisational: Reed writes the plays, with additional material from Ker. This volume collects three of their productions, which originally appeared on Radio 4: Macbeth Rebothered (2014), The Odyssey (2015) and The Curse of the Beagle (2016). A typically appreciative Radio 4 audience is audible throughout, and adds to the atmosphere. Volume one was published concurrently, but, since it looked to be more focused on spoofing actual history, I went straight to the more obviously fantastical volume two. Margaret Cabourne-Smith appears in all three stories, performing most of the female roles, and getting many of the best lines. Susan Calman, Robert Webb, Greg McHugh and Lolly Adefope also take part.

Tuesday 21 August 2018

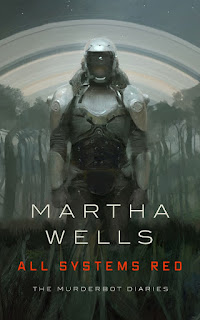

All Systems Red, by Martha Wells (Tor.com) | review by Stephen Theaker

People are using wormholes to travel to distant planets, and since that can be a dangerous business their insurers tend to insist that the expeditions include a so-called murderbot (a SecUnit) to do any necessary killing. They also record every conversation for later data-mining. One of these robots is our protagonist, and since it has hacked the governor module that would normally keep it under control the explorers don’t realise how much danger they are in. Luckily for them, the murderbot prefers soap opera to grand guignol. Less luckily, someone or something else has tampered with their equipment and data. When a competing base on the other side of the world goes dark, the murderbot accompanies the scientists on a trip to investigate, while trying to deal with the social anxiety that inevitably results from spending time with people who at any moment could rumble its secrets and have it disassembled. They freak out enough even when seeing it has a humanoid face under its helmet. This is a short, very enjoyable book about an anti-hero who can take a lot of damage and keep on going, who almost despite itself starts putting others ahead of its own interests; a bit like Wolverine or Snake Plissken but with the insecurity that comes from its particular circumstances. Placing a character like that in a terribly dangerous scenario with ruthless villains on the loose and a bunch of decent scientists to protect makes for good reading. The fight scenes are very well worked, and so is the evolution of the robot’s relationships with its colleagues/leaseholders. I doubt this’ll be the last book I read about this robot. ****

Sunday 19 August 2018

Iron Fist, Season 1, by Scott Buck and chums (Marvel/Netflix) | review by Stephen Theaker

Joy (Jessica Stroup) and Ward Meachum (Tom Pelphrey) are the siblings who run the immense multinational Rand Corporation, which was founded by Wendell Rand (who died with his family in a plane crash) and their unpleasant father (David Wenham), who died of cancer. A problem presents itself: a homeless man (Finn Jones) turns up at their building, claiming to be Danny Rand, son of their father’s partner, and an old friend of theirs. If it is Danny Rand, he would own 51% of their company. At first they don’t believe him, to the extent that they throw him out without asking a handful of obvious questions that could have easily confirmed his identity.

Wednesday 15 August 2018

The Meg | review by Rafe McGregor

Size matters.

I first watched Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) on the small screen in the late seventies or possibly in 1980 or 1981 – some time in the second half of my first decade. I don’t remember the year or whether my experience was courtesy of videotape or 8mm film, but I do remember being absolutely, completely, and utterly terrified. So scared that for a weeks I was reluctant to bath, let alone swim in a pool. That didn’t last, but the fear of sharks did. Not exactly clinical galeophobia or even enough to keep me from swimming in the sea, but enough to cause some of the physical symptoms of the phobia for nearly four more decades of seeing sharks on film and in dreams. As is well known, Jaws became the prototypical Hollywood blockbuster and its form, style, and content have been emulated with more or less success for forty-three years. The film also became a franchise, spawning three sequels with diminishing critical and commercial returns: the best thing about Jaws 2 (1978) was its tagline (“Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water”); Jaws 3-D (1983) was as disappointing as the other attempts to revive 3D cinema in the early eighties; and Jaws: The Revenge (1987) was nominated for eight Golden Raspberry Awards, achieved a rare but well-deserved 0% on the Tomatometer, and showed that even the great Michael Caine can make poor career choices. None of the four were, however, financial failures and the shark movie was soon established as a subgenre of the horror film.

I first watched Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) on the small screen in the late seventies or possibly in 1980 or 1981 – some time in the second half of my first decade. I don’t remember the year or whether my experience was courtesy of videotape or 8mm film, but I do remember being absolutely, completely, and utterly terrified. So scared that for a weeks I was reluctant to bath, let alone swim in a pool. That didn’t last, but the fear of sharks did. Not exactly clinical galeophobia or even enough to keep me from swimming in the sea, but enough to cause some of the physical symptoms of the phobia for nearly four more decades of seeing sharks on film and in dreams. As is well known, Jaws became the prototypical Hollywood blockbuster and its form, style, and content have been emulated with more or less success for forty-three years. The film also became a franchise, spawning three sequels with diminishing critical and commercial returns: the best thing about Jaws 2 (1978) was its tagline (“Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water”); Jaws 3-D (1983) was as disappointing as the other attempts to revive 3D cinema in the early eighties; and Jaws: The Revenge (1987) was nominated for eight Golden Raspberry Awards, achieved a rare but well-deserved 0% on the Tomatometer, and showed that even the great Michael Caine can make poor career choices. None of the four were, however, financial failures and the shark movie was soon established as a subgenre of the horror film.

Tuesday 14 August 2018

Pawn: A Chronicle of the Sibyl’s War, by Timothy Zahn (Tor) | review by Jacob Edwards

A chronicle of discontent.

This is not so much a review as a lament. Timothy Zahn used to be a favourite author of mine. I own many of his books. But in recent years I find myself borrowing, not buying (and even then I do so more from inertia than with the thrill of expectation). Perhaps the fault is mine, and my tastes have moved on. Or maybe Zahn has grown too comfortable in his niche.

This is not so much a review as a lament. Timothy Zahn used to be a favourite author of mine. I own many of his books. But in recent years I find myself borrowing, not buying (and even then I do so more from inertia than with the thrill of expectation). Perhaps the fault is mine, and my tastes have moved on. Or maybe Zahn has grown too comfortable in his niche.

Sunday 12 August 2018

Into the Unknown: a Journey Through Science Fiction, curated by Patrick Gyger (Barbican) | review by Stephen Theaker

This exhibition, billed as “the genre-defining exhibition of art, design, film & literature”, began running at the Barbican on 3 June 2017 (the day the TQF co-editors and their families attended), and would remain open until 1 September 2017. It was announced in 2016, and I had been looking forward to it ever since, but in the event it was, despite some remarkable exhibits, a bit of a disappointment. Part of that can perhaps be laid at the tickets, which promised three parts, but only the first was the exhibition proper, and there wasn’t very much of it.

Tuesday 7 August 2018

John Wyndham: BBC Radio Drama Collection, by John Wyndham et al. (BBC Worldwide) | review by Stephen Theaker

This marvellous audiobook collects five full-cast BBC adaptations of John Wyndham’s classic science fiction work – five novels, plus a short story – as well as Beware the Stare, a half-hour documentary from 1998. It’s a ten-hour journey into some catastrophes that are not at all as cosy as I remembered.

Sunday 5 August 2018

Eastercon 2017: Innominate | review by Stephen Theaker

I only attended for two days of this four-day convention, Saturday and Monday. It took place in Birmingham in April 2017, at a hotel close to the NEC, near enough for me to travel to in an hour or so on public transport, so I had bought a full membership fairly early on without knowing whether I would be free or not. My daughter and I attended on Saturday. I bought her a one-day ticket at a very reasonable rate. She was interested in attending a talk on manga and anime, and a session on painting alien worlds, and enjoyed them both. We also watched the BSFA awards, which were good, convivial fun, and then the first episode of Doctor Who season ten, which was shown on three huge screens in the main events room.

My daughter enjoyed herself enough to recommend the event to my younger daughter, my wife, and the two children of my co-editor, so they all came with us on the Monday. Upon arriving we had the nice surprise of discovering that my older daughter’s painting from the Saturday session had won a prize in the children’s art show, which got the day off to a great start. It was a banner day too for my younger daughter, who for the very first time in her life, after being asked for her name, had someone recognise it and say, “Oh, like Telzey Amberdon.”

That day we attended hair-braiding and journal decoration sessions, which were interesting, even for those of us without hair or journals (the hair I lost long ago; the journal I gave away to a little girl who didn’t have her own). Between the two workshops we attended the closing ceremony, which must have been an odd experience for the four members of our group who had only arrived an hour and a half before.

Not staying at the hotel overnight, only attending a couple of panels, not being there for the full four days, and not really talking to anyone in the bar, I suppose most people would say I didn’t properly get stuck into the convention, but I’d still say it was my favourite convention experience yet. A few years ago I said to an occasional TQF contributor that I didn’t really like conventions. He told me that perhaps I had been going to the wrong ones, and after this weekend I think he may have been right.

On the surface this convention was almost completely indistinguishable from the last one I attended in York (my favourite convention before this one), but a few small and significant differences emerged over the couple of days. The strand of events for children was one. (If we’d realised there was a Lego Minifigure event on Sunday we’d have gone on that day too.) It also seemed to have more fans as opposed to career-orientated writers (something at least one writer has grumbled about). And we didn’t hear anyone bellowing across the convention rooms like territorial wildebeests.

Course, my experience of other cons is probably coloured to some extent that I went there to present various reports to the AGMs, and watch the awards I’d administered play out, appear on panels a couple of times, and one time be the secretary and treasurer for the whole bleeding thing, whereas Eastercon was pure relaxation, nothing to do except listen to clever people talk about things (Aliette de Bodard was a standout contributor to both panels I attended) or watch the children get on with fun and creative activities.

Best of all, there were plenty of places to sit when nothing was happening. Sofas everywhere, a quiet room, a fan lounge; it really contrasted well with all the times I’ve been at conventions and struggled to find somewhere to sit and read my new books. There was no goody bag, and no convention souvenir book, two things some attendees of other cons care very deeply about, but I wasn’t at all bothered by their absence. The daily newsletters about convention occurrences were great fun.

If Eastercon returns to Birmingham we’ll definitely go again, and I think we enjoyed it enough that we could even be tempted a bit further afield. ****

My daughter enjoyed herself enough to recommend the event to my younger daughter, my wife, and the two children of my co-editor, so they all came with us on the Monday. Upon arriving we had the nice surprise of discovering that my older daughter’s painting from the Saturday session had won a prize in the children’s art show, which got the day off to a great start. It was a banner day too for my younger daughter, who for the very first time in her life, after being asked for her name, had someone recognise it and say, “Oh, like Telzey Amberdon.”

That day we attended hair-braiding and journal decoration sessions, which were interesting, even for those of us without hair or journals (the hair I lost long ago; the journal I gave away to a little girl who didn’t have her own). Between the two workshops we attended the closing ceremony, which must have been an odd experience for the four members of our group who had only arrived an hour and a half before.

Not staying at the hotel overnight, only attending a couple of panels, not being there for the full four days, and not really talking to anyone in the bar, I suppose most people would say I didn’t properly get stuck into the convention, but I’d still say it was my favourite convention experience yet. A few years ago I said to an occasional TQF contributor that I didn’t really like conventions. He told me that perhaps I had been going to the wrong ones, and after this weekend I think he may have been right.

On the surface this convention was almost completely indistinguishable from the last one I attended in York (my favourite convention before this one), but a few small and significant differences emerged over the couple of days. The strand of events for children was one. (If we’d realised there was a Lego Minifigure event on Sunday we’d have gone on that day too.) It also seemed to have more fans as opposed to career-orientated writers (something at least one writer has grumbled about). And we didn’t hear anyone bellowing across the convention rooms like territorial wildebeests.

Course, my experience of other cons is probably coloured to some extent that I went there to present various reports to the AGMs, and watch the awards I’d administered play out, appear on panels a couple of times, and one time be the secretary and treasurer for the whole bleeding thing, whereas Eastercon was pure relaxation, nothing to do except listen to clever people talk about things (Aliette de Bodard was a standout contributor to both panels I attended) or watch the children get on with fun and creative activities.

Best of all, there were plenty of places to sit when nothing was happening. Sofas everywhere, a quiet room, a fan lounge; it really contrasted well with all the times I’ve been at conventions and struggled to find somewhere to sit and read my new books. There was no goody bag, and no convention souvenir book, two things some attendees of other cons care very deeply about, but I wasn’t at all bothered by their absence. The daily newsletters about convention occurrences were great fun.

If Eastercon returns to Birmingham we’ll definitely go again, and I think we enjoyed it enough that we could even be tempted a bit further afield. ****

Saturday 4 August 2018

Willful Child by Steven Erikson | review by Stephen Theaker

“Dad! First contact! Vulcans!” “Wish it was, boy,” Harry replied. “More like… idiots.” Three-eyed aliens visiting Earth in the “Age of Masturbation” leave behind a spaceship and get us started on a programme of galactic expansion. A century or so later Captain Hadrian Alan Sawback finagles his way into command of the starship Willful Child. He’s a terrible sexist, obsessed with trying to have sex with the female crew members and making sure male crew members know their place: not on away missions and well out of the limelight.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)