Wednesday 28 December 2016

The Savage Sword of Conan, Vol. 14, by Charles Dixon, Gary Kwapisz, Ernie Chan and chums (Dark Horse Books) | review by Stephen Theaker

This reviewer has read several volumes in this series over the last year or so, and this review could pretty much apply to any of them, since The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian was a remarkably consistent magazine. Whichever collection you pick up, you’ll get the same black-and-white mix of a rough but honourable barbarian, extremely attractive women (variously good and evil), mad wizards and kings, and reliably good storytelling and art – all for a bargain price. One improvement is that by the issues collected here, 141 to 150, the black caption boxes that made the earliest books rather a pest to read are long gone, and the creative team of Dixon, Kwapisz and Chan have settled in for a run of consecutive issues that tell a series of consecutive stories in Conan’s life. As ever, each individual story, whether it is teaming up with Red Sonja on a quest for a hidden idol, defending a fort from a Pictish attack, or a struggle in Brythunia to prevent the rising of Oranah, the Stag God, who drives farmers mad with murderlust, has the length and heft of a French album, but this time they also add up to more, a grand saga that takes Conan from a gladiator to a general and beyond. One story, “Blind Vengeance”, features a firm but unfair tyrant who intimidates villagers into handing over their goods, and carves a W into the foreheads of corpses – an inspiration for Negan on The Walking Dead, perhaps? The speech balloon placement is a bit careless, with the correct reading order often counterintuitive and confusing, but the artwork is nearly always top notch, and unusually for a Comixology edition double page spreads are presented as two separate pages, which makes it much easier to read on a tablet. Recommended to anyone who liked any of the other volumes. ****

Monday 26 December 2016

Chobits Omnibus, Vol. 1, by CLAMP (Dark Horse) | review

Hideki is a college kid who is trying to get into Tokyo university, and he doesn’t have a lot of money. He certainly can’t afford a persocom, a human-shaped computer, so it seems like a stroke of luck when he finds one that’s apparently been thrown out with the trash. She seems to be in good condition, and is, incidentally, very pretty, though Hideki is more focused on spreadsheets, word processing and household accounting (by all of which he means pornography). As he carries her off, a disk falls out, and maybe this is why she has no memories, and not even an operating system. He names her Chi, because at first that’s all she says. She’s a blank slate for Hideki’s lessons, and since he’s a buffoon that doesn’t go well; she ends up unwittingly working for a short spell at a strip club. As the endless pages fly by, she seems to develop feelings for him, while he does for her, even as he is told by himself and others that she’s a machine and such feelings are a waste. Would he be better off spending his time with Yumi Omura, a peppy student with a crush on him? Then there’s Takako Shimizu, a college tutor who turns up at his house for an impromptu sleepover, and Chitose Hibiya, his beautiful landlady, who is keeping a couple of big secrets, and knows a few about Chi, who might be one of the fabled Chobits, persocoms that can learn for themselves. Although this manga translation is presented in the now-traditional right-to-left format, the limited amount of dialogue per page stops it from being too confusing to read. The backgrounds are plain, as little art as possible being used to fill each page – the printing costs that have shaped US comics so much were presumably less of an issue as comics developed in Japan. I’ve never before read a book so long in which so little happens. It only took a couple of hours to read, despite being 740pp long. (This explains those fifteen-year-old Goodreads users with thousands of books read.) The “sexy” elements of it tend to be a bit gross, especially in retrospect after we’re told late in the book the apparent age of Chi’s physical body. It has some interesting ideas about how easily humans would switch their affections to such androids, sidestepping the problems and complexities of human romance. It’s undemanding, occasionally amusing, a bit pompous, and it kept me busy while I drank a cup of tea; if volume two comes up in a sale I might possibly buy it, but otherwise I’d be happy to leave Hideki to perv over his personal computer in private. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday 21 December 2016

Kalpa Imperial, by Angelica Gorodischer (Small Beer Press) | review by Stephen Theaker

Subtitled “the greatest empire that never was”, this book tells a series of stories about the long-lived empire of Kalpa – or so we presume, since that name only appears in the title. In the book it is just the Empire, and it has a north, and a less easily governed south, and it has lasted (or will last: some stories hint that this is a future empire) so long that emperors and even dynasties may be completely unknown to their successors. Some stories, like “The Old Incense Road”, about an elderly man leading traders across the desert, take place over a shortish span of time, but others are rather more expansive, like the remarkable “And the Streets Deserted”, which follows a city from its founding and shows its many different lives, as an imperial capital, as a home for artists, as a spa for the unwell. Each story brings a majesty to the lives great and small that it examines, and each is equally enjoyable. The rule in the Empire is much like that for the original run of Star Trek films, that emperors will, in general, alternate between the good and the bad, and the book shows us both. The wisdom and determination of the Great Empress Abderjhalda in “Portrait of the Empress” or the emperor who never leaves his bedroom in “The Two Hands” are an example of each. The book was originally published in two volumes in Argentina in 1983, and this translation by Ursula K. Le Guin, which seems, so far as one can tell without reading the original, to be impeccably done, is from 2003. It should appeal to anyone with a taste for the epic, and in particular readers who enjoyed Lucius Shepard’s The Dragon Griaule, with which it shares many similarities: of tone, structure, and indeed quality. *****

Monday 19 December 2016

Atomic Robo, Vol. 7: The Flying She-Devils of the Pacific, by Brian Clevinger and Scott Wegener (Tesladyne) | review

Atomic Robo is a cool guy created by Nikolai Tesla, who he calls his dad. He is atomic-powered, generally good-natured, and likes a fight. He’s strong, wry, almost indestructible, and each graphic novel (or mini-series, in their original publication) takes us to a different period of his life, with different friends and colleagues, previous highlights including battles with giant Nazi robots and cthulhoid monsters. If that sounds a lot like Hellboy, that’s because it is a lot like Hellboy – but with blue skies and daylight. Book seven begins with him flying an experimental plane in 1952, and under attack by weird little flying tanks. Not having any weapons and badly outnumbered, he gets shot down and would be destroyed were it not for a squadron of rocket-women. They kept fighting in the Pacific rather than going home to countries where they’d have to hang up their bomber jackets, their enemies mostly mercenaries, but now there’s a bigger threat, and they’re going to need Atomic Robo’s help to stop it. The previous six Atomic Robo books were all very good, and given that this is once again from the same writer and artist it isn’t a surprise that this is too. A few panels left me puzzling a little over what was going on, but when I dawdled it was more often to take it all in. The rectangular panels make it ideal for reading on a tablet. Reading one one Atomic Robo book always makes me want to read all of them again. The only sad thing is that the skipping about in time means we’re not likely to meet the she-devils again for a while, a shame because they’re rather brilliant. Stephen Theaker ****

Saturday 17 December 2016

Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #57: now out, in print and ebook!

free pdf | free epub | free mobi | print UK | print US | Kindle UK | Kindle US

Issue fifty-seven of Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction is now out!

It is one hundred and sixty-eight pages long, and features five tales of fantasy, horror and science fiction: “The Elder Secret’s Lair” by Rafe McGregor, “Nold” by Stephen Theaker, “On Loan” by Howard Watts, “The Battle Word” by Antonella Coriander, and “With Echoing Feet He Threaded” by Walt Brunston. The spectacular wraparound cover is by Howard Watts, and the editorial includes exciting news about the magazine’s plans for 2017. The issue also includes forty pages of reviews, and some sneaky interior art from John Greenwood.

In the Quarterly Review, Stephen Theaker, Douglas J. Ogurek, Jacob Edwards and Rafe McGregor consider audios written by Colin Brake, Jonathan Morris, Justin Richards and Marc Platt, books by Cate Gardner, Erika L. Satifka, Harun Siljak, Joe Dever and Karl Edward Wagner, and comics from Joshua Williamson and Fernando Dagnino, G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona, and Erik Larsen, plus the films Don’t Breathe, Ghostbusters: Answer the Call, Ouija: Origin of Evil and Suicide Squad, and the television programmes Preacher season one and The X-Files season ten.

Here are the kindly contributors to this issue:

Antonella Coriander is not so sure about this. “The Battle Word” is the eighth episode of her ongoing Oulippean serial, Les aventures fantastiques de Beatrice et Veronique.

Douglas J. Ogurek’s work has appeared in the BFS Journal, The Literary Review, Morpheus Tales, Gone Lawn, and several anthologies. He lives in a Chicago suburb with the woman whose husband he is and their pit bull Phlegmpus Bilesnot. Douglas’s website can be found at: http://www.douglasjogurek.weebly.com.

Howard Watts is a writer, artist and composer living in Seaford who provides both a story and the amazing wraparound cover art for this issue. His artwork can be seen in its native resolution on his deviantart page: http://hswatts.deviantart.com. His novel The Master of Clouds is now available on Kindle.

Jacob Edwards also writes 42-word reviews for Derelict Space Sheep. This writer, poet and recovering lexiphanicist’s website is at http://www.jacobedwards.id.au. He has a Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/JacobEdwardsWriter, where he posts poems and the occasional oddity, and he can be found on Twitter too: https://twitter.com/ToastyVogon.

Rafe McGregor is the author of The Value of Literature, The Architect of Murder, five collections of short fiction, and over one hundred magazine articles, journal papers, and review essays. He lectures at the University of York and can be found online at https://twitter.com/rafemcgregor.

Stephen Theaker’s reviews, interviews and articles have appeared in Interzone, Black Static, Prism and the BFS Journal, as well as clogging up our pages. He shares his home with three slightly smaller Theakers, no longer runs the British Fantasy Awards, and works in legal and medical publishing.

Walt Brunston’s adaptation of the classic television story, Space University Trent: Hyperparasite, is now available on Kindle.

As ever, all back issues of Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction are available for free download.

Issue fifty-seven of Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction is now out!

It is one hundred and sixty-eight pages long, and features five tales of fantasy, horror and science fiction: “The Elder Secret’s Lair” by Rafe McGregor, “Nold” by Stephen Theaker, “On Loan” by Howard Watts, “The Battle Word” by Antonella Coriander, and “With Echoing Feet He Threaded” by Walt Brunston. The spectacular wraparound cover is by Howard Watts, and the editorial includes exciting news about the magazine’s plans for 2017. The issue also includes forty pages of reviews, and some sneaky interior art from John Greenwood.

In the Quarterly Review, Stephen Theaker, Douglas J. Ogurek, Jacob Edwards and Rafe McGregor consider audios written by Colin Brake, Jonathan Morris, Justin Richards and Marc Platt, books by Cate Gardner, Erika L. Satifka, Harun Siljak, Joe Dever and Karl Edward Wagner, and comics from Joshua Williamson and Fernando Dagnino, G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona, and Erik Larsen, plus the films Don’t Breathe, Ghostbusters: Answer the Call, Ouija: Origin of Evil and Suicide Squad, and the television programmes Preacher season one and The X-Files season ten.

Here are the kindly contributors to this issue:

Antonella Coriander is not so sure about this. “The Battle Word” is the eighth episode of her ongoing Oulippean serial, Les aventures fantastiques de Beatrice et Veronique.

Douglas J. Ogurek’s work has appeared in the BFS Journal, The Literary Review, Morpheus Tales, Gone Lawn, and several anthologies. He lives in a Chicago suburb with the woman whose husband he is and their pit bull Phlegmpus Bilesnot. Douglas’s website can be found at: http://www.douglasjogurek.weebly.com.

Howard Watts is a writer, artist and composer living in Seaford who provides both a story and the amazing wraparound cover art for this issue. His artwork can be seen in its native resolution on his deviantart page: http://hswatts.deviantart.com. His novel The Master of Clouds is now available on Kindle.

Jacob Edwards also writes 42-word reviews for Derelict Space Sheep. This writer, poet and recovering lexiphanicist’s website is at http://www.jacobedwards.id.au. He has a Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/JacobEdwardsWriter, where he posts poems and the occasional oddity, and he can be found on Twitter too: https://twitter.com/ToastyVogon.

Rafe McGregor is the author of The Value of Literature, The Architect of Murder, five collections of short fiction, and over one hundred magazine articles, journal papers, and review essays. He lectures at the University of York and can be found online at https://twitter.com/rafemcgregor.

Stephen Theaker’s reviews, interviews and articles have appeared in Interzone, Black Static, Prism and the BFS Journal, as well as clogging up our pages. He shares his home with three slightly smaller Theakers, no longer runs the British Fantasy Awards, and works in legal and medical publishing.

Walt Brunston’s adaptation of the classic television story, Space University Trent: Hyperparasite, is now available on Kindle.

As ever, all back issues of Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction are available for free download.

Wednesday 14 December 2016

Archivist Wasp, by Nicole Kornher-Stace (Big Mouth House) | review by Stephen Theaker

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the best way to begin a novel is with a fight to the death, and that is how this novel begins. Wasp is the current archivist, her job being to capture ghosts and record what information she can glean from them. This miserable and lonely existence has a downside: each year she is challenged by three upstarts to a knife fight. If one of them wins, they’ll become the archivist, and she’ll become a ghost. If she wins, she has to tie a braid of their hair into her own, making her head heavier by the year, giving her headaches, making it more likely that she will lose to the children.

Monday 12 December 2016

Doctor Who: The Angel’s Kiss, by Melody Malone (BBC Books) | review

River Song is in New York, working as a private eye under the name Melody Malone, just as we found her at the beginning of the television episode, “The Angels Take Manhattan”. She takes the case of a minor film star, Rock Railton, who has overheard someone saying that he will die. Then she runs into a fellow who looks like him on the street, dying, and extremely old. At a party she meets him again, young and beautiful but without the slightest idea who she is. Weird stuff is going on and she wants to figure it out whether she gets paid or not. This short book, written in truth by Justin Richards, doesn’t match the passages quoted from it on television, sadly, but it does lead nicely into that story, and it gives River Song a lot of fun things to say and do. The audio version, read by Alex Kingston herself, must be a hoot. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday 7 December 2016

X-Men: Apocalypse, by Simon Kinberg | review by Stephen Theaker

The events of X-Men: Days of Future Past have changed the timeline, and everyone now knows about mutants. Mystique is a hero to her kind, a civil rights leader who runs an underground railroad to help the less fortunate among them, such as Nightcrawler, forced to fight in a cage match against a very angry Angel. Back in Westchester, Professor Xavier has got his school for the gifted up and running, and when Magneto resurfaces, recruited by Apocalypse during a vulnerable moment, Mystique goes to Xavier for help. Cyclops and Jean Gray are already there, learning to control their powers, and Quicksilver is on his way – he also wants to find Magneto, albeit for different reasons. It’ll take the lot of them to cope with Apocalypse, an ancient body-swapping, power-collecting mutant who has just escaped from his underground prison of thousands of years. He’s a tough cookie and he can be very persuasive. It is time for the X-Men to go into action for the very first time all over again, and that is part of this film’s joy, to see a team very close to that of the Claremont/Byrne years of the comic in action: Cyclops, Jean Gray, Beast, Nightcrawler, Professor Xavier and even Storm, though she’s on the wrong side for much of the film, Apocalypse having found her in this timeline in Cairo before Xavier got around to it. It’s great to see them together, and that contributes to this feeling like the most X-Meny of the X-Men films yet. X2: X-Men United may have been a better film overall, but it felt like a science fiction film based on the idea of the X-Men whereas this feels like the X-Men. The melodrama, the humour, the flips from one side to the other, the bravery and tragedy: it’s all here. Once again Quicksilver comes close to stealing the film. Psylocke is introduced, but her complicated backstory is perhaps wisely left to one side, so there’s no sign of her brother Captain Britain, sadly. Another much-loved character makes an extremely violent five-minute cameo that may leave parents wondering whether it was wise to bring children to the film, as well as wondering how it ties up with the conclusion of the previous film – but continuity has never really been a concern of these films. See how badly the end of The Wolverine lines up with the beginning of Days of Future Past, or the constant recasting of any character not played by Hugh Jackman. By this ninth film in the series, including all spin-offs, that discontinuity must be taken as read. Let’s just assume there are changes to the timeline going on constantly in this movie universe, not just those we see on screen. It’s not perfect by any means – the tears over the lost cast of X-Men: First Class seem insincere given the film-maker’s decision to give them the boot. The post-credits scene is a colossal letdown, leaving the cinema audience audibly deflated (ironic for a film that credits its inflatable audience wranglers). But overall it was probably my favourite X-Men film yet. It rounds off this prequel trilogy nicely, James McAvoy being especially fantastic as Professor Xavier, while setting things up very well for what could be a new set of films featuring the classic line-up in their youth. I’m looking forward to the next film much more than I was looking forward to this one. ***

Arrival | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

The lingo of time: UFO film touches down as one of year’s most impressive cinematic offerings.

I didn’t think that any film this year would stack up to 10 Cloverfield Lane. So much for that. Arrival offers another strong female lead in an equally gripping sci-fi masterpiece.

The latter film, directed by Denis Villeneuve, in many ways transcends its genre to become, in this reviewer’s opinion, an Oscar contender. Inherent in the title is the film’s big idea. This isn’t an Independence Day or War of the Worlds alien invasion action film. It’s merely an arrival of extraterrestrial vessels, and protagonist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) must decode the aliens’ language.

I didn’t think that any film this year would stack up to 10 Cloverfield Lane. So much for that. Arrival offers another strong female lead in an equally gripping sci-fi masterpiece.

The latter film, directed by Denis Villeneuve, in many ways transcends its genre to become, in this reviewer’s opinion, an Oscar contender. Inherent in the title is the film’s big idea. This isn’t an Independence Day or War of the Worlds alien invasion action film. It’s merely an arrival of extraterrestrial vessels, and protagonist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) must decode the aliens’ language.

Monday 5 December 2016

How a Ghastly Story Was Brought to Light by a Common or Garden Butcher’s Dog, by Johann Peter Hebel (Penguin Classics) | review

This fifty-three page book manages to pack in twenty-six short stories, as told by Your Family Friend. The back cover describes them as “fables, sketches and tall tales”, but it may remind readers of The Real Hustle, which showed BBC viewers how con artists separate the greedy from their money. These stories would have performed a similarly useful duty for the readers of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, stories like “A Stallholder Duped” and “The Weather Man” showing the kind of tricks people might play. Two favourite stories of mine were “One Word Leads to Another”, in which a man asks what has been happening at home, and, as is so often is the case, the answer “Nothing much” turns out to be an understatement, and “A Secret Beheading”, a strange and terrible tale in which an executioner is kidnapped by unknown parties to do his usual work in a private matter. The back cover tells us that one of these twenty-six stories was Franz Kafka’s favourite, but doesn’t say which – that one, or perhaps the title story, about a pair of two-time murderers, would be my guess. Hebel writes, at least as translated here by John Hibberd and Nicholas Jacobs, much like Rhys Hughes, albeit without the fantasy. See especially “Strange Reckoning at the Inn”, where three clever students try to convince a cleverer-than-they-think pub landlady that since time is a circle and they do not have money to pay their bill, she should be patient and wait for them to return in six thousand years with the money they owe. She points out that they still owe her for the meal they ate six thousand years before. Stephen Theaker ****

Thursday 1 December 2016

Well, that went badly. #nanowrimo

- You didn't do a chapter plan. This always works very well for you, so why didn't you do it this time? I suspect it's because you knew it would be hard because you didn't have a plot. You knew what the book was going to be about, what its theme would be, but you didn't think about what would actually happen from one chapter to the next. Next time plan the whole thing from start to finish, at least vaguely.

- You did that thing again, that you do every time, where you begin the novel with a character on their own, with no one to talk to, in a featureless location where nothing is happening! In 2017 start your book with twenty people having an argument in a ghost house or something.

- You tried to write a novel based on stuff that you were still quite fed up about, so whenever you tried to think about the novel you just got fed up about the thing you were fed up about, all over again. That didn't work. Don't do it next time.

- You refused to relinquish the hour or so you spend watching tv each evening with your lovely lady wife. Yes, it's been great for your relationship over the last twenty years to have that time together each evening, drinking hot chocolate and laughing, crying, etc depending on the show, but if that had been sacrificed you'd have had another 30 hours or so to write your novel. And it only takes you about 50 hours to write your stupid little novels.

- You forgot how much your own books make you laugh. Yes, they're terrible, but you should have had a read of one before this month started to remind yourself how hilarious you (if no one else) find them, to encourage you to write another, for your own entertainment if no one else's.

- Your protagonist and your antagonist were the wrong way around. Yes, you wanted to write a novel about someone making a lot of bad decisions leading to a galactic disaster, but wouldn't you have found it much easier to write about the adventures of the chap being put in a series of tight spots by those bad decisions? There's a reason Spider-Man is the star of the comic book rather than J. Jonah Jameson.

- You made the classic error of planning to write less Monday to Friday and more over the weekends. November is birthday season! You aren't writing more at the weekends. You're struggling to write anything! In 2017, stick to the plan: 1666 words a day, every day.

Well, Stephen of 2017, I hope you take all of that on board, and do a better job than you did this time. I have my doubts, given that this year you didn't read any of the brilliant advice I left for me in previous years…

Wednesday 30 November 2016

Star Trek: Gold Key Archives, Vol. 1, by Dick Wood, Alberto Giolitti and Nevio Zeccara (IDW Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

Back when the William Shatner version of Captain James Kirk first commanded the USS Enterprise, Gold Key published these cheesy but energetic stories about him and his crew; even in those early days for the franchise, half-Vulcan first officer Spock must have been the clear breakout character, since he appears more prominently than the captain on four of the six covers. Tony Isabella explains in the introduction that none of the creators involved in this series saw any episodes before starting work, which may explain why Scotty is in these issues an awkward blonde, and why in “The Planet of No Return” an encounter with a plant civilisation ends with the planet being scoured of all life, on Spock’s urgent recommendation. In “The Devil’s Isle of Space” the crew nonchalantly leaves convicts to be killed in an explosion, simply because it is “the way of their society”. These are big-scale stories where anything goes. In “Invasion of the City Builders”, a planet’s land has been almost completely covered by cities, thanks to automation gone too far, and “The Peril of Planet Quick Change” features missiles being fired into the planet’s core. In “The Ghost Planet” the ship drags the rings away from a planet, and in “When Planets Collide” the ship must somehow stop two worlds from crashing into each other, an impact which would pitch many of the planets of the Alpho galaxy “out of orbit… to burn in space!” Galaxies seem to be quite small here, and the ship seems to visit a new one every issue! Time is measured in lunar hours and galaxy seconds, everyone in the universe speaks Space Esperanto, and Kirk calls aliens “space scum”. So the stories are goofy, but that only makes them more enjoyable. It does capture that sense from the original series that the universe was an incredibly dangerous place where even heroes like Kirk and Spock would only survive if luck was on their side. The newly recoloured art looks great, and the simple six-panel grid layout makes for very easy reading. ***

Monday 28 November 2016

A Slip Under the Microscope, by H.G. Wells (Penguin Classics) | review

The precise definition of science fiction has always been a matter for debate, the simplest answer being the stuff H.G. Wells wrote about. With books like The Time Machine (time travel), The First Men in the Moon (space travel), The War of the Worlds (alien invasion), The Shape of Things to Come (future history), The Invisible Man (experimentation on oneself) and The Island of Doctor Moreau (experimentation on others) he staked out the territory of a genre that still thrives, still finds new places to go, almost seventy years after his death. This fifty-five page Penguin Little Black Classic contains two of his short stories which don’t quite fit that narrative. The title story, “A Slip Under the Microscope” is science fiction of the other kind, a story about science, where a driven young student, labouring under the pressure of being a working class boy at the College of Science, where pupils on scholarships are not even invited to sit down when meeting their tutors, makes a terrible mistake during an examination. The other story, “The Door in the Wall”, is more fantastical, about a government minister who longs for the secret garden he found as a child, the magical entrance to which only ever presents itself again when he has not the time to enter it. Both stories are very, very good. The first couple of Little Black Classics I read – As Kingfishers Catch Fire by Gerard Manley Hopkins and Aphorisms on Love and Hate by Friedrich Nietzsche – were dreadful, but it’s clear I judged the series too soon. Stephen Theaker ****

Ten free ebooks from the paperback library!

- Five Forgotten Stories, John Hall

- His Nerves Extruded, Stephen Theaker

- Pilgrims at the White Horizon, Michael Wyndham Thomas

- Professor Challenger in Space, Stephen Theaker

- Quiet, the Tin Can Brains Are Hunting! Stephen Theaker

- Space University Trent: Hyperparasite, Walt Brunston

- The Day the Moon Wept Blood, Stephen Theaker

- The Doom That Came to Sea Base Delta, Stephen Theaker

- The Fear Man, Stephen Theaker

- The Mercury Annual, Michael Wyndham Thomas

Snap them up!

Saturday 26 November 2016

Journey into Space: Frozen in Time, by Charles Chilton (BBC Audio/Audible) | review

This fifty-seven minute adventure is the fifth Journey into Space. The first three, Operation Luna, The Red Planet and The World in Peril, were long, episodic sagas broadcast in the fifties, while the last three, The Return from Mars, Frozen in Time and The Host were radio plays broadcast in 1981, 2008 and 2009 respectively. All were written by Charles Chilton, except The Host. As this story begins the usual crew of Captain “Jet” Morgan, “Doc” Matthews, Mitch and Lemmy are on their way back from Neptune in the Ares. The cast is all new except David Jacobs, who played several supporting characters in the original trilogy, often in the same scene, and here plays Jet Morgan. A problem with his cryogenic sleep unit meant Jet has been awake for practically the whole thirty-year trip home, and a good thing too or the ship might well have been destroyed. He wakes the others as they approach Mars, long-forgotten and short on fuel. They land near the Saviour 1, itself stuck there after developing a fault. Good thing Mitch is here, since in this distant future of 2013 it’s unusual for a crew to include an actual engineer. The media rep and the health and safety officer aren’t much good at fixing spaceships. The captain is now a “flight manager”, and Doc notes with bemusement how the remaining crew of the Saviour 1 spend all their spare time playing games on their screens. (If Charles Chilton could see us now!) They seem unwell, and there are clues to suggest that they’ve been up to no good... This story keeps the mood of the originals very well, remarkably so given the fifty years that had passed when this was produced, and that’s helped by the use once again of Doc’s diary entries to bridge narrative gaps. The crew all behave in recognisable ways, even down to the flashes of the old irritation with each other at times of stress. It’s just a shame that it stops after one hour, instead of ten. Stephen Theaker ****

Wednesday 23 November 2016

Star Trek, Vol. 1, by Mike Johnson, Stephen Molnar and Joe Phillips (IDW Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

The ongoing Star Trek comic follows the adventures of the Chris Pine version of Captain James Kirk and his crew, as shown in Star Trek XI, XII and XIII. This first volume collects issues one to four, set soon after the eleventh film, with Kirk in charge of the USS Enterprise a good deal sooner than in the previous continuity, and the five year mission off to an early start. Oddly, though, they still run into many of the same situations, since the two stories here are adapted from the television episodes “Where No Man Has Gone Before”, in which crewman Gary Seven acquires the powers of a god after the Enterprise tries to cross the galaxy’s edge , and “The Galileo Seven”, in which a shuttlecraft crew led by an as-yet untrusted Spock is lost and stranded on a dangerous world with aggressive locals. James Blish’s prose adaptations tended to improve on the original programme, so maybe these comics could do the same? Sadly not. Adapting forty-minute episodes to forty-page comics doesn’t leave room for a lot of detail, and although the stories are subtly changed by taking place in the new continuity they feel sketchy and underfed. The artwork is good, the likenesses pretty decent, it’s just that the project itself feels a bit pointless. Perhaps it’s aimed at fans of the new films who haven’t watched the original show? Either way, it’s good to see that subsequent volumes add new, original stories to the mix. **

Monday 21 November 2016

Wailing Ghosts, by Pu Songling (Penguin Classics) | review

Translated by John Minford, these are fourteen very short fantasy stories and tall tales, written by a Chinese author who lived from 1640 to 1715. They are set in a world of fox spirits, demons and red-headed monsters. The book doesn’t explain its humanoid foxes, but they seem to be like those in The Heavenly Fox by Richard Parks, where foxes who lived to the age of fifty could assume human form, and those who lived to a thousand became immortal. Because the stories are so short, it’s difficult to say much about them without giving away the entire plot, but the highlights include “King of the Nine Mountains”, about a man who rents his back garden out to a party of a thousand fox spirits and promptly betrays them, and “Butterfly”, where a syphilitic horny teenager, Luo Zifu, “breaks out in suppurating sores, which left stains on the bedding” and is thus driven out, eventually to find happiness with Butterfly, a supernatural lady who lives in a grotto. He blows it, of course. Other stories include “The Monster in the Buckwheat”, “Scorched Moth the Taoist”, “The Giant Turtle” and “A Fatal Joke”, which is barely a page long but features the book’s most horrible image. When a book this good costs 80p, you’d be daft not to buy it. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday 18 November 2016

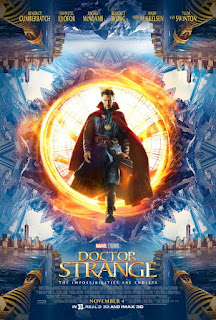

Doctor Strange | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Top-notch acting meets special effects in world-hopping tale of narcissist’s downfall and rebirth.

Full disclosure: I am not a comic book nerd, and I knew nothing about Doctor Strange before seeing the latest Marvel blockbuster that bears his name. I am, however, quite familiar with the acting talents of Benedict Cumberbatch, Tilda Swinton, and Chiwetel Ejiofor. So it was with great enthusiasm that I anticipated this superhero origin film. The wait paid off.

Full disclosure: I am not a comic book nerd, and I knew nothing about Doctor Strange before seeing the latest Marvel blockbuster that bears his name. I am, however, quite familiar with the acting talents of Benedict Cumberbatch, Tilda Swinton, and Chiwetel Ejiofor. So it was with great enthusiasm that I anticipated this superhero origin film. The wait paid off.

Wednesday 16 November 2016

The Last Weekend, by Nick Mamatas (PS Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

Even before the collapse, Vasilis Kostopolos was not a nice guy, and not a happy guy either. A self-loathing alcoholic who follows an ex-girlfriend to Boston, who follows random women on the subway while abusing them in his mind, who doesn’t mind if the money he spends on drink helps fund the IRA, he ends up in San Francisco, a surprisingly good place to be when the dead start to rise. There are no cemeteries there, and the zombies struggle with the big hills. He’s a writer, and he can prove that with the print-out of his one published story that he keeps in his pocket at all times, but he takes a job as a driller. When the dying seem likely to turn, he gets a call. If he’s lucky, he gets there once they’re dead but before they’ve revived, but he’s rarely lucky. Turns out he’s pretty good at the job, or at least he doesn’t quit or get eaten. He’s a guy who spent his “adult life trying to avoid adult life, living a simplified version of it without dreams of a family”. Before the collapse he would consider killing himself “a dozen times a day, maybe more”. So when everything falls apart for everyone else (at least in the USA; nowhere else seems to be affected) he copes pretty well, his life hasn’t got much worse. (Also a theme of the later show Fear the Walking Dead, where a junkie adapts better to the apocalypse than the rest of his family.) He even starts to meet women: Alexa, who shoots a boy who jumps out at them, pretending to be a zombie; Thunder, a friend of the dead boy who shamelessly steals Vasilis’s stuff; Jaffe, a civil servant who kept on serving after the collapse. Thunder and Alexa share a desire to get to the bottom of things, to uncover the mysteries of the apocalypse, to find out what the government (such as it is) is hiding, and Vassily gets mixed up in their plans despite himself. This is a terrific book, the kind of thing you might expect if McSweeney’s had a horror imprint, intelligent, provoking, self-aware, and full of interesting ideas. You wouldn’t ever want to be this guy, as a writer, or as a human being, but you can understand why he survives, and why it takes the breakdown of human society for him to write his great American novel. ****

Monday 14 November 2016

Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange, translated by Malcolm C. Lyons (Penguin Classics)

This is a collection of medieval Arabian fantasy, or at least half of it, the other half being lost to the sands of time. Malcolm C. Lyons provides a new translation, rendering the book rather more readable than the excellent and informative (but spoiler-heavy – read it after the rest of the book) introduction by Robert Irwin suggests the original to be. On Goodreads a potential reader has asked whether the book is suitable for children, and the answer is most definitely no. Grimdark a thousand years before George R.R. Martin or Joe Abercrombie, this is brutal, horrible and cruel, stories of terrible people doing awful things in a world ruled by capricious and sentimental tyrants. Racists, rapists and murderers, these characters lie, cheat and steal their way to happy endings, often saved by a last-minute religious conversion or appeal to a deity. That the stories are about such awful people wouldn’t be so jarring if it weren’t for the religiosity of it all. Irwin cautions against “the enormous condescension of posterity”, quoting E.P. Thompson, and that’s a fair point, but it’s hard to really enjoy stories in which slavery and sexual aggression are so positively portrayed. For example, in “The Story of Sakhr and Al-Khansa’ and of Miqdam and Haifa’”, Sakhr sneaks into a girl’s tent and draws his sword, saying “if you utter a word I shall make you into a lesson to be talked of amongst all peoples breaking your joints and your bones”. The girl “saw that he was handsome as well as eloquent; she weakened and looked down bashfully as he got into bed with her”. That’s fairly typical, and that story gets worse. The book is also quite repetitive, with everyone who is half-decent to look at being described as like the moon, Indian swords all over the place, people hitting themselves in the face all the time, and every man being “delighted” to discover that his copulative partners are still virgins. (In one case, that’s even though they slept together earlier in the story.) That’s not to say there’s nothing to enjoy here. Though women are generally shown in a terrible light and treated horribly – for example, a king is told the story of ‘Arus al-’Ara’is to make him glad his daughter died! – several are shown to live independently and drink wine very happily. It was surprising to see an acknowledgment of the existence of gays and lesbians, even if it was to discourage such romances, and in the story of the Foundling and Harun al-Rashid there are heavy hints of male romance. “No one is going to rub him down except me,” says the executioner Masrur in a bath-house. The story of Miqdad and Mayasa shows the former killing enemies like a supercharged Conan the Barbarian and the desert being rolled up for the latter. In the story of Julnar of the Sea a king says of a gorgeous woman, “Praise be to God, Who created you from a vile drop in a secure place!” A nice way of putting it. The story of Abu Disa is amusing: a browbeaten weaver is pushed into posing as an astrologer, and through various turns of fortune makes a series of astonishing and lucrative predictions. The story of Sa’id Son of Hatim al-Bahili is a fascinatingly curious attempt to retcon the Bible. Overall, though, I found the book such a struggle to get through that I wouldn’t recommend it on its own merits as a collection of stories; they’re just not very good; but as a curiosity, as a glimpse into the storytelling of the past, as a translation and as a historical artefact it may find appreciative readers. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday 9 November 2016

The Zombies That Ate the World, Vol. 1: An Unbearable Smell! by Jerry Frissen and Guy Davis (Humanoids) | review by Stephen Theaker

This digital album tells four of the “everyday occurrences that happen in the twilight of Los Angeles”, to quote the line that ends them all. It is 2064 and the dead have been coming back to life. They aren’t violent, at least no more than they were when they were alive, and so the government has decreed that the living and the dead must live peacefully together. That’s going pretty well until Otto Maddox, a filthy rich man with extremely expensive hobbies, has an actor disinterred, Franza Kozik. When alive, she starred in such films as Queen of the Zombies and Flesh Feast, and once out of her coffin she picks up where she left off, eating brains, but for real this time, and that inspires other zombies to try it too. The other stories here include a historian of the twentieth century who wants his reanimated father-in-law peacefully disposed of, and a Nazi type who wants the brain of a particular zombie rewired to restore its intelligence. All four stories feature, to a greater or lesser extent, Karl Heard, who with his sister Maggie and their hulking associate The Belgian, makes a barely legal living as a zombie catcher. Elsewhere, Christians are executing thousands of people in the Holy Land in hopes of persuading Jesus to return, and a scientist has reanimated a dinosaur. This is an odd book, with a humorous tone that sits a bit uneasily with the tawdry and horrible stories it is telling, but it is worth reading, especially for the art of Guy Davis, who readers might know from Sandman Mystery Theatre or The Marquis. His style of drawing is exceptionally well-suited to the portrayal of the rotting undead, not to mention the other sleazy types in the book. ***

Monday 7 November 2016

Ouija: Origin of Evil | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Will this prequel overcome its predecessor’s mediocrity? Yes.

This Halloween season, horror film fans had slim pickings at the theatre. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, like me, they felt disappointed when they learned about the season’s feature offering: Ouija: Origin of Evil.

This Halloween season, horror film fans had slim pickings at the theatre. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, like me, they felt disappointed when they learned about the season’s feature offering: Ouija: Origin of Evil.

Arrow, Season 2, by Marc Guggenheim and many others (Warner Bros Television) | review

Oliver Queen was a sleazy rich kid who took his girlfriend’s sister away on a disastrous yacht trip, leaving him marooned on an island, from which he was rescued five years later. He returned with a new set of skills, and a new sense of purpose, determined to use his archery and acrobatics to take down the wealthy one percenters who have been bleeding the city dry. Unfortunately, the first season of Arrow was in its early stretches often indistinguishable from stablemate Gossip Girl, but as its roster of costumed characters built up it improved, an episode with the Huntress attacking her father’s compound being particularly good, and it ended well, with a serious threat that pushed the fledgling hero to his limits. Season two is even better, putting Oliver and his night-time nom de guerre under an ever-tightening screw, as a friend from the past returns with a grudge. Flashbacks to the island continue, moving more or less in pace with current-day events, creating an unusual effect whereby the viewer must constantly rethink the Oliver we met in the programme’s first episode. DC fans will appreciate the introduction of a certain group of villains sent on deadly missions by (the remarkably slim) Amanda Waller, and by the end Black Canary is in it so much they could have put her name in the titles. Supporting characters Diggle and Felicity are also given plenty to do, though Oliver’s family and friends, especially his mother and Laurel, tend to zig and zag rather randomly whenever the plot requires it. The season draws on classic New Teen Titans, and from there brings us one of the best villains yet in a television superhero series. Despite Felicity’s best efforts, there isn’t much humour, and the dialogue is rarely more than functional; the thrilling story just about makes up for it, but one hopes John B. Arrowman plays a bigger part in seasons to come. In his few scenes here he displays a totally welcome cheekiness that was rather buried in season one. Stephen Theaker ***

Wednesday 2 November 2016

Marshals, Book 1: Darkness and Light, by Dennis-Pierre Filippi and Jean-Florian Tello (Humanoids) | review by Stephen Theaker

Hisaya is a marshal on the planet Iriu, working in an area under the control of the air consortium. Her robot partner is wrecked during the apprehension of a former robo-trafficker, but her grandad can’t supply her with a replacement this time: he’s switched to making buxom humanoid pleasure bots (though they can fight when needed, and it will be needed). Instead he introduces her to Tetsu, a young mechanic with a passion for robotics who has built a nifty new defence bot – and she can have it if she will take Tetsu on as an apprentice. A five-page naked sauna scene with the pleasure bots later, and Marshal Hisaya returns to the city with her new apprentice and her new bot, just in time for a series of treacherous attacks that will leave everyone running for their lives. Darkness and Light is the first of four digital albums, also collected in a single hardcover book from the same publisher. It does a good job of setting up this steampunky, Final Fantasyesque world, and Marshal Hisaya is quite the badass. The nude scenes feel a bit redundant and pandering, and it isn’t always easy to follow the action, but in general the art is very appealing and characterful, a bit reminiscent of Ian Gibson’s 200AD work, with the extra detail that working on an album rather than weekly pages can allow. The colours, by Studio Bad@ss, do a great job of picking out all that detail and letting the eye make sense of it all. A good start to the series. ***

Monday 31 October 2016

The Flash, Season 1, by Andrew Kreisberg and many others (Warner Bros Television) | review

The Flash is a name that has been used by a series of DC Comics characters: Jay Garrick in the forties, Barry Allen from the late fifties, Wally West from the late eighties, and probably a couple more since. The Flash of this television series is Barry Allen, a police scientist who is struck by lightning and becomes the fastest man alive. Before that happened Barry appeared in episodes of Arrow, and so, like the forthcoming Legends of Tomorrow and Vixen animated series this is part of what’s sometimes called the Arrowverse. Gotham probably isn’t a part of this continuity, nor was Smallville, nor are any of the planned DC films, but Supergirl is in a nearby dimension, and Constantine was added after-the-fact once he had appeared in Arrow. That’s quite the little universe that has grown out of Arrow, a show with such unpromising beginnings. The Flash gets off to a much better start than its big brother. The big change from the comics (or at least the comics I’ve read) is that the lightning storm is brought on by an explosion at STAR Labs, after Harrison Wells turns on his particle accelerator against the advice of his colleagues. This explosion acts much like the meteor crash in Smallville, providing an origin for most of the superpowered beings we meet in the programme. (One whose powers don’t come from there is Captain Cold, played brilliantly by Wentworth Miller in several episodes.) Wells, along with high-flying assistants Cisco Ramon (Carlos Valdes) and Caitlin Snow (Danielle Panabaker), helps Barry to master his powers, as step by step he becomes the Flash we know and love. Grant Gustin is likeable as Barry Allen, determined to clear his father for the murder of his mother (he saw red and yellow blurs flashing around her in the room that night...), and in love with journalist Iris West, daughter of the police officer who became his guardian once dad was in jail. There is so much to like about the show: its confident handling of story arcs and mysteries, its excellent special effects, the speed with which it builds up a roster of great supporting characters, the diversity of its cast and characters, and how it draws on all the riches of the character’s history. This is Barry Allen, but there’s a lot of the Wally West stories in here too: fingers crossed for Chunk in season two! For those who have read Flashpoint, the risk that this Barry might create that dark universe looms over the season’s events. The main villain is properly scary, with his glowing red eyes and readiness to kill. I could live with less mooning over Iris in season two, but the programme originates on The CW so that rather goes with the territory. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday 28 October 2016

Y: The Last Man, Vol. 4: Safeword, by Brian K. Vaughan, Pia Guerra, Goran Parlov, and José Marzań, Jr (Vertigo) | review by Stephen Theaker

Yorrick Brown is left alive after a plague killed every other man in the world – and every male creature but one, his monkey Ampersand. In this fourth book, collecting issues 18 to 23 of the original series, he is still travelling across America with Dr Allison Mann and Agent 355. They hope to reach Mann’s lab and figure out his immunity, and find a way for the human race to start reproducing again. That’s the long-term plan, but right now Ampersand is ailing from the cut he picked up in the previous book. While Agent 355 and Dr Mann go off to get medicine, they leave Yorick with one of 355’s retired colleagues, Agent 711. His experiences in her log cabin are eye-opening, to say the least, and we learn that Yorick isn’t quite the happy-go-lucky type we had imagined. In the book’s second story, “Widow’s Pass”, the interstate route is blocked by a small but heavily-armed militia, convinced the government is behind the plague and ready to beat any government employees to death until they confess. It’s another terrific volume of this series. The story is gripping, both in the day to day events and the ongoing mysteries. The artwork and colouring is perfect, the action always totally understandable without giving up any dynamism. And this book gives us many more layers to Yorick’s character, as we learn more about his life both before and immediately after the disaster. Best of all is the thoughtful storytelling of the sort that gives us Dr Mann explaining which animal species will die out first, because of their short life cycles: the apocalypse isn’t yet over. Very good indeed. Stephen Theaker ****

Wednesday 26 October 2016

The Hounds of Hell, Book 1: The Eagle’s Companions, by Philippe Thirault and Christian Højgaard (Humanoids) | review by Stephen Theaker

During the sixth century CE, the Emperor Justinian reigns in Byzantium, but dreams of reclaiming the western Roman empire, which has fallen to the barbarians. Angles and Saxons here in the UK, Vandals in Corsica and North Africa, Visigoths in Spain, and Ostrogoths in Italy: Theodoric, king of the Goths, has been named imperial regent. Justinian’s young wife, Theodora Augusta, a worshipper of Pluto, sets in motion a plan. Epidamnos, the warrior-magus, also called Avian, is tasked with reuniting his colleagues, the most fearsome band of mercenaries to ever exist. Or at least those of them that survive: there was a reason they split up. Camarina the Panther, deposed princess of Thrace; Triada, an Amazonian archer (called here the archeress); the Eagle, a scarred general: he summons them all by means of their Edessa stones. Khorsabad Three-Hands he recovers from a prison in the district of thieves. Their mission: to recover the treasure offered by the Roman emperors to the old gods as an apology for ditching them in favour of Christianity. Or at least that’s what they think. This digital album is the first in a series of four (all of which are also available in a single paperback collection), and it does a good job of drawing the team together, showing us what is special about each of them, and getting them started on their adventures, as well as dipping back into their histories. There’s some unpleasant sexual violence, but otherwise it’s an exciting, intriguing adventure that is impeccably drawn and coloured. ***

Monday 24 October 2016

Y: The Last Man, Vol. 1: Unmanned, by Brian K. Vaughan, Pia Guerra and José Marzán, Jr (Vertigo) | review

Every man and boy in the world starts throwing up blood and drops down dead, all at the same time. Is it because the Amulet of Helene has been taken out of Jordan, bringing on an ancient prophecy of catastrophe? Or because Doctor Mann gave birth to her own clone? Or because Yorick Brown proposed to his best friend with a ring he bought in a magic shop for half the money he had? The only man who might find out is Yorick himself, because he’s the only man to survive (at least so far as we know from this book). All the male non-humans died too, except for his capuchin monkey Ampersand. Others might have seen the resulting situation as a golden opportunity for a healthy young man, but not Yorick, he’s in love with Beth, and she’s in Australia, so like James Garner in Support Your Local Sheriff that’s where he’s heading, whatever else distracts him in the meantime. It’s a dangerous world for a man, where anyone he meets could want to sell, kill or enslave him, but his mother asks him to go with the awesome Agent 355 to find Dr Mann – together they might be the best hope for the world, especially if they can figure out why Yorick survived. This is an excellent book. It has a great premise, and this volume begins to explore the ramifications of that premise in fascinating ways. For example, Yorick’s mother is a representative in Congress, and because the Democrats have more female representatives there than the Republican, they become a majority when the men die. Pia Guerra and José Marzán, Jr’s art is perfect, reminiscent in its clarity and structure of Steve Dillon’s work on Preacher for the same publisher, but with character all of its own. The book’s weakest link is probably Yorick himself, who isn’t half as interesting and charismatic as the female characters that surround him. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday 21 October 2016

Jessica Jones, Season 1, by Melissa Rosenberg and chums (Marvel/Netflix) | review by Stephen Theaker

Jessica Jones is a private eye, and she’s down on her luck, doing jobs for a shady lawyer that don’t always bring out her best side. Traumatised by having fallen under the mental control of a powerful psychic for a long period, and the things he forced her to do during that time, she’s drinking too much and not looking after herself. She has a couple of things going for her: superstrength (though no more invulnerability than is required to punch people very hard without breaking your own arm) and a good friend, former child star Patsy Walker. (Their friendship and its history is one of my favourite things about the programme.) Sadly, we’re not joining Jessica at the point where things start to pick up for her. She does meet a new guy, Luke Cage, who seems able to deal with the worst drunks in Hell’s Kitchen without taking a scratch, but it’s not one of those relationships built on mutual trust, at least at first. And she’s beginning to think that Kilgrave, her psychic tormentor, might be back, and it’s impossible to make anyone believe her when he can just order people to forget that they’ve ever seen him. He is back (and played with a gleefully childish lack of conscience by David Tennant), and he’s going to cause a lot of trouble before the thirteen-episode series is over.

Wednesday 19 October 2016

Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe, by Thomas Ligotti (Penguin Classics) | review by Rafe McGregor

In issue forty-nine I reviewed Thomas Ligotti’s The Spectral Link (2014) and described him as the most accomplished practitioner of weird fiction today. As such, it is satisfying to see that he has finally been admitted to the canon of twentieth century horror fiction by inclusion in the Penguin Classics series, which has recently taken an interesting turn with the publication of relatively obscure works of classic pulp horror fiction, like Clark Ashton Smith’s The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies (2014). This is particularly satisfying in Ligotti’s case as although he is in his fourth decade of publishing to great critical acclaim, he has failed to achieve mainstream success – understood in terms of mass market paperback sales. I think there are two reasons for this: although he has published sixteen books to date (excluding the Penguin release, but not The Spectral Link), they have all been collections of short stories, short novellas, or poetry rather than the novel so beloved by commercial publishers. Second, there is the – and I know no better term – weirdness of the stories themselves, which I imagine will not have an appeal beyond horror aficionados in the way that, for example, Stephen King’s work does. Ligotti has nonetheless remained a firm favourite of a limited audience and I was lucky enough to pick up Volume 9, Number 1 (1989) of the long-abandoned Crypt of Cthulhu magazine, with nine short pieces by him, at a recent book fair. The price was very reasonable – too reasonable – and I wish there was more demand for his work.

Monday 17 October 2016

Doctor Who, Season 9, by Steven Moffat and friends (BBC) | review

Peter Capaldi returns for a second season as the Doctor, Jenna Coleman for a third as Clara, and Steven Moffat for his fifth as head writer. Not a surprise then that this feels like the work of people who really know what they are doing with these characters. The Doctor at first is travelling alone, having the party of his life in medieval times because he knows there’s trouble up ahead, while Clara is teaching at Coal Hill, where it all began. They are brought back together by Missy, Davros and the Daleks, and by the end of the year they’ll have encountered Odin, the Zygons, ghosts in an undersea base, an immortal girl running a sanctuary for aliens, and the creatures that grow from the sleep in your eyes if you leave it unwashed for too long. They’ll travel to the very end of the universe and back, while ending every other episode on a cliffhanger.

Friday 14 October 2016

Fear the Walking Dead, Season 1, by Robert Kirkman and chums (AMC) | review by Stephen Theaker

Travis Manawa (played by Cliff Curtis) and Madison Clark (Kim Dickens) are a married couple trying without much luck to blend a family. He is divorced, she is a widow. Travis has a son who lives with his ex and doesn’t want to see him at the weekends, Madison has a son, Nicky, who loves heroin and a daughter, Alicia, who hates long trousers. When Nicky wakes up in a drug den to find his girlfriend eating someone’s face, he thinks he’s gone mad, and so does his family, but it won’t be long before everyone is caught up in that madness. When a riot breaks out in the city centre, Travis and his son take refuge in a hairdressers with a family of three, emigrants from El Salvador, not realising that from now on, all refuge will be temporary.

Wednesday 12 October 2016

A Song of Shadows, by John Connolly (Hodder & Stoughton) | review by Rafe McGregor

A Song of Shadows (464pp, £3.85) is the thirteenth “Charlie Parker thriller”, as the series is described by Hodder & Stoughton, first published in hardback in 2015. First and foremost – and quite possibly because of rather than in spite of the criticisms I shall make – the series is extremely successful, regularly ranking high on various bestseller lists and regularly receiving rave ratings from the most trusted crime fiction reviewers. I must confess to not having read all of Parker’s cases, which began with Every Dead Thing in 1999 (and was, as an example of my previous claim, the L.A. Times Book of the Year), but I have read the first two and most recent two and can confirm that there has been no fluctuation in quality. Connolly is not one of those writers who rests on his laurels, resorts to repeated uses of the same formula, or tires of his protagonist. My gripe, and I think it is more than mere whimsy on my part, is the idiosyncratic mix of crime and horror Connolly has weaved around Parker.

Monday 10 October 2016

Trials Fusion Awesome Max Edition, by RedLynx (Ubisoft) | review

The Trials series of games are, to the casual glance, so simple that they could have been made on a Spectrum, and, indeed, pretty much were, as fans of Codemasters’ ATV Simulator will remember. You’re just driving a bike along a straight line that sometimes goes up, sometimes goes down, while you lean back and forth to keep it balanced. It’s like the old TV show Kickstart, except you can’t even turn the handlebars. And yet that’s just on the surface. The Trials games put that simplest of ideas into a world built with individual objects and subject to physics, where the slightest nudge here or there can make the greatest difference, and where your rider dies horribly at the end of each level. On some levels it’s a thrill ride, hurtling down a snowy mountain like you’re chasing James Bond, while on harder levels it’s the world’s toughest platformer, as you take a hundred attempts to get over one gnarly jump. And since the levels (once you get the hang of them) only take a few minutes to complete, the games are endlessly replayable in search of a better time. This Xbox One expansion of Trials Fusion improves upon the Xbox 360 version to the extent that it’s well worth a separate purchase. It includes all the DLC, so immediately has an immense range of tracks to ride on, from deserts and ski resorts to various distant, destroyed futures. To cap it all there’s a series of incredible levels where you play as a cat riding a unicorn! These were so popular with my children that one suspects an entirely equestrian spin-off could be very popular – they also liked being able to create a female rider for the regular levels. Another improvement is that loading times are much improved. Part of the appeal of Trials HD was the way you could rattle through half its levels in a half hour lunch break, something lost in the slovenly Xbox 360 version of this game. The checkpoints in Trials Fusion are much closer together than they were in Trials HD, making it possible to muddle your way through hard levels in a way that would have been impossible before. At first this seems disappointing, a sop to lightweights, but it’s as hard as ever to set a good time, and it’s easy to understand why the game’s makers would want lots of players to see all of the cool stuff they have created. And for anyone who misses the real teethgrinding challenges of old, the extreme difficulty levels here are as hard as ever – I’ve yet to pass the first checkpoint in any of them. The game also includes a brilliant local four-player multiplayer mode (allow bailout finishes for maximum fun), a level creator and online game modes, including tournaments where you post your best time and then wait to see where you came, prizes being awarded to those who reach certain positions. I’ve yet to mention what a pretty game it is, but it is, and it really shines with the higher definition of a next-generation console. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday 7 October 2016

Ash vs Evil Dead, by Ivan Raimi and chums (Starz/Virgin Media) | review by Stephen Theaker

Ash Williams is a sexist jerk with an unfortunate tendency to unleash the forces of hell upon the world. Thirty years ago he found a Necronomicon while on a trip to a cabin in the woods with his girlfriend, and ended up having to squash her head in a vice and cut off his own hand with a chainsaw. Neither has forgiven him. As this ten-part series starts, the Deadites have been quiet for a while, but he still keeps a boomstick in his mobile home. It proves handy after the idiot gets high with a sozzled friend and reads from his Necronomicon… The evil dead return in force, and so Ash, reluctantly, gathers friends to help in the fight. It’s all a bit daft – the spirits seem to be able to take over anybody whenever they like, so the only reason Ash survives is presumably because they like playing with him – but it doesn’t quite reach the stark raving lunacy of Evil Dead II. There are lots of good jump scares, some excellent monsters and one-liners, and it is refreshingly gory. The half hour format works well for the show – it would be hard to keep up the intensity for an hour. Ash’s boorishness and the misogyny of the language used when female characters are possessed is partly balanced by a diverse cast. Ash develops an appealing relationship with Special Agent Fisher, an African-American cop who seems to like him for the idiot that he is, and the scenes with his two likeable protégés are always watchable – they’re a bit like the Doctor, Rory and Amy, if the Doctor were a buffoon and Rory worshipped him anyway. ***

Wednesday 5 October 2016

Innerspace, by Jeffrey Boam and Chip Proser (Warner Bros. et al.) | review by Jacob Edwards

Dir. Joe Dante. 1 July 1987 (Amblin Entertainment). Genre: SF Comedy. Ratings: 81% (Rotten Tomatoes) 6.7 (IMDB).

Obstreperous test pilot Tuck Pendleton (Dennis Quaid) volunteers for a miniaturisation experiment that should see him and his ship injected into the bloodstream of a laboratory rabbit. Instead, thanks to some industrial espionage gone badly wrong, he finds himself inside hypochondriac no-hoper Jack Putter (Martin Short). Aided by Pendleton’s ex-girlfriend, journalist Lydia Maxwell (Meg Ryan), and guided from within by Pendleton himself, Putter must overcome his inhibitions, thwart the villains and recover the microchip necessary to extract the ship before Pendleton’s oxygen runs out.

Obstreperous test pilot Tuck Pendleton (Dennis Quaid) volunteers for a miniaturisation experiment that should see him and his ship injected into the bloodstream of a laboratory rabbit. Instead, thanks to some industrial espionage gone badly wrong, he finds himself inside hypochondriac no-hoper Jack Putter (Martin Short). Aided by Pendleton’s ex-girlfriend, journalist Lydia Maxwell (Meg Ryan), and guided from within by Pendleton himself, Putter must overcome his inhibitions, thwart the villains and recover the microchip necessary to extract the ship before Pendleton’s oxygen runs out.

Monday 3 October 2016

Showcase Presents Ambush Bug, by Keith Giffen, Robert Loren Fleming and friends (DC Comics) | review

A 488pp black and white collection of comics, mostly from the mid-eighties. The bulk of it comes from two mini-series, Ambush Bug (1985) and Son of Ambush Bug (1986), plus a couple of specials, his story from Secret Origins, and earlier guest appearances in Superman titles. Ambush Bug is the costumed identity of Irwin Schwab, who knows he’s in a comic, talks to his writers and artists, and doesn’t necessarily go from one page to the next in the usually accepted order. His best friend and adopted child is Cheeks the Toy Wonder, a stuffed toy, and his greatest foes are the Interferer, who messes with comics continuity because he can, and Argh-Yle, a sock from a spaceship that got squashed by a radioactive space-spider, came to life and became a supervillain, and now tries to conquer the world with living socks from a chest of drawers (The Bureau) orbiting the planet. Reading that back, it’s hard to understand why I didn’t like it very much. It sounds like a lot of fun, and Deadpool has had great success with a similar shtick. But I laughed only three or four times in the course of all these pages (the best being when Keith Giffen’s famous nine-panel layouts are said to be inspired by Celebrity Squares). Maybe it’s the lack of colour in this edition, which makes all the busy, busy pages a bit hard to read, or that there’s so much frantically packed in, which might have worked better taken in single issue doses. A lot of the humour is aimed at comics and controversies in the field from the mid-eighties, and though I’ve read enough of those to get the gist, I didn’t find them funny. Maybe the clue is in the panel five pages from the end where Ambush Bug declares “I hate British humour”. Though I do appreciate the cleverness there of spelling it with a U. Stephen Theaker **

Friday 30 September 2016

Ex Machina Book One, by Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris (Vertigo) | review by Stephen Theaker

The mayor of New York isn’t a Republican or a Democrat. He was a superhero, and before that an engineer, sent to investigate something weird and green glowing underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. Whatever it was blew up in his face, and he gained the ability to talk to machines and (perhaps more usefully, since we can all do that) have them follow his instructions. He grew up reading Justice League of America comics, so naturally, with the addition of a rocket pack, helmet and alien blaster, he became the Great Machine. It didn’t go very well, and after his secret identity was blown he decided to run for mayor, to put himself in a position where he could effect real change. He won, though not for reasons he would ever have wanted, and now he’s trying to run a city where psychos want to kill him, the commissioner of police and the state governor both hate him, and a publicly-subsidised gallery is about to display a painting of Abraham Lincoln with a racist word scrawled across his chest. His powers are only going to help with some of those problems. This 273pp book collects the first eleven issues of the original comic, and it got off to a terrifically confident start. The narrative bounces around the mayor’s timeline without ever confusing, and mixes ongoing plots with shorter self-contained stories with an apparent ease that must have required a good deal of work. The artwork is striking and unusual, looking almost as if photographs of actors have been rotoscoped to produce it. However it was produced, the result can be peculiar, but only because it has led to such a surprisingly varied range of expressions, faces and poses. I’d read parts of this book before, out of order, borrowed from the library, but it’s a real treat to start from the beginning, knowing I have books two to five waiting to be read in my Comixology library. The entire set cost me just £15 in a sale. I won’t often get the chance to spend my money more wisely. ****

Wednesday 28 September 2016

The Devil’s Detective, by Simon Kurt Unsworth (Del Rey) | review by Rafe McGregor

Back in issue twenty-four, I reviewed Mark Valentine’s The Black Veil and Other Tales of Supernatural Sleuths (2008), an anthology that has since come to define the specific area of overlap between crime fiction and speculative fiction known as either the supernatural sleuth or the occult detective. In his introduction, Valentine explains how the magazine contributors of the late nineteenth century began to explore different ways in which the relatively new and incredibly popular figure of the private detective could be merged with the much older but still entertaining milieu of the ghost story. This combination of detective protagonist and ghostly setting saw the initial blossoming of the subgenre, which included such greats as Arthur Machen’s Mr Dyson, Robert Eustace and L.T. Meade’s John Bell, E. and H. Heron’s Flaxman Low (the Herons were actually the Prichards, a mother and son team), Algernon Blackwood’s Dr John Silence, and William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki.

Monday 26 September 2016

Don’t Breathe | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

So tense it doesn’t need a true protagonist.

Don’t Breathe, a turn-the-tables tale about three burglars who become their blind victim’s prey, offers no superb dialogue, no complicated internal struggles, and no computer-generated imagery-heavy superhero battles.

Don’t Breathe, a turn-the-tables tale about three burglars who become their blind victim’s prey, offers no superb dialogue, no complicated internal struggles, and no computer-generated imagery-heavy superhero battles.

Friday 23 September 2016

Days Missing, by Phil Hester, Frazer Irving and chums (Archaia) | review by Stephen Theaker

The Steward is a white-haired guy who fights like Neo and (theoretically) exists outside of time in a colossal library, watching our world go by. When a particularly disastrous day comes around, he steps in, to inspire people, to fight them, to cover up his own existence, and presumably sometimes just to relieve the boredom of spending eternity on his own. If he can fix things before the day is done, smashing, but more often he has to rewind time by twenty-four hours and reshape events. It’s as if Bill Murray in Groundhog Day learnt to activate his time-looping ability on demand. The day lost in the loop may echo in the feelings and dreams of those that live on – for example, Mary Shelley in one story, whose encounter with a reanimated corpse inspires Frankenstein – but otherwise the only record of that lost day is in the books that line the Steward’s library. He was alive before humanity existed, and seems likely to long outlive us, but he’ll do his best to keep us going. Do you have any idea how long he spent trying to talk to dinosaurs before we came along?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)