Matt Murdock is a blind lawyer affronted by the injustice he sees in his home of Hell’s Kitchen, a part of New York damaged badly in the battle between the Avengers and Loki’s army of alien invaders. Property developers are moving in, but some of the current inhabitants don’t want to move out, and that’s the kind of case that the newly established firm of Nelson and Murdock can be persuaded to take. What the two lawyers don’t know at first is that behind it all is a shadowy kingpin, who is bringing together Russian, Chinese and Japanese gangsters in one great criminal enterprise. Anyone who dares to utter his name – Wilson Fisk – is killed for their indiscretion, making it impossible to pin anything on him. It would be an impossible situation were it not for Matt’s unusual abilities. The chemicals that took his sight enhanced all his other senses – taste, touch, hearing and balance – and he was trained in combat, at least for a time, by the mysterious Stick. These skills let Matt fight for the city, at first in a black mask, and by the end of the series in the distinctive red suit of Marvel’s Daredevil.

This is an extremely violent series, much more so than Agents of SHIELD or Agent Carter, not suitable at all for children. Matt Murdock tends to get very badly wounded, since he’s often fighting against the odds. A fight in the second episode is the best I’ve ever seen on television, like looking down the classic corridor scene in Oldboy. Wilson Fisk is an utterly brutal villain, his fists the piledrivers they are in the comics, Vincent D’Onofrio’s performance so chilling, so physical and intense, that he’d have had awards nominations if this wasn’t a series about a superhero. (I hope we’ll see him face off against the Avengers or Spider-Man or Daredevil himself on the big screen at some point.) It draws on many periods of the comics, in particular those written by Frank Miller, Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Waid, to create a classic version of the character. The mood is dingy and grim, though Foggy brings just the right amount of humour to stop it getting too gruelling – and were those the stilts of Stilt-Man I saw in the background of one scene? Its pace is very much its own; this couldn’t be a network show, with the constant need to cue up adverts that has made programmes like The Big Bang Theory little more than a series of vignettes. The episodes stretch out fully over their running length, building up to moments of sudden, shocking violence. My only grumble is about the frequent discussions about the existence or not of god (Matt Murdock being a Catholic and Wilson Fisk an atheist), which seem bizarre given that the season’s plot follows on from a battle between Loki and Thor. Would people keep believing in other gods, or for that matter remain atheists, when real gods have been seen on television? Perhaps they would, but it makes Matt seem a bit daft. But that’s just a minor issue. I wouldn’t just rate this higher than the other Marvel television series, I’d rate it higher than most of the movies. And season two is going to feature the Punisher and Elektra! Let’s hope a change of showrunner doesn’t put a billy club in the works. Stephen Theaker ****

Monday, 28 March 2016

10 Cloverfield Lane | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Character, tension reign in masterwork of claustrophobic uncertainty.

The mind-numbing sameness of many films has trained viewers to expect a narrow list of possibilities as a story unfolds… either this will happen or that will happen… character x is either all this or all that. 10 Cloverfield Lane, directed by Dan Trachtenberg and based loosely on the alien attack extravaganza Cloverfield (2008), plays upon this tendency to pigeonhole outcomes and characters. Set mostly in a bunker beneath a Louisiana farm, the film serves up a potent “he’s coming/who’s out there?” tension gumbo whose ingredients range from bold (and sometimes shocking) actions to more ordinary, yet still highly charged situations.

The mind-numbing sameness of many films has trained viewers to expect a narrow list of possibilities as a story unfolds… either this will happen or that will happen… character x is either all this or all that. 10 Cloverfield Lane, directed by Dan Trachtenberg and based loosely on the alien attack extravaganza Cloverfield (2008), plays upon this tendency to pigeonhole outcomes and characters. Set mostly in a bunker beneath a Louisiana farm, the film serves up a potent “he’s coming/who’s out there?” tension gumbo whose ingredients range from bold (and sometimes shocking) actions to more ordinary, yet still highly charged situations.

Friday, 25 March 2016

Star Wars: The Force Awakens, by Lawrence Kasdan and chums | review by Jacob Edwards [spoilers]

Déjàvooine Sunrise.

Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens (if we may be allowed a scrolling preamble) has been released with considerable fanfare and after much anticipation. Like the birth of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, its arrival brings together a nation of fans united in pride, patriotism, hope and nostalgia (and, be warned, young George, with a bevy of concealed weapons held at the ready). At last! A renewal of the franchise that blew up the box office in 1977 and grew quickly to become – for some people quite literally – a cinematic religion. But those who queue for midnight screenings do so with some trepidation. Given the false dawn of the prequelogy (Episodes I–III), will this merely be more of the tepid same? How will the new film tie in with the Expanded Star Wars Universe? Will the original characters return and stay true to memory three decades on? Will director J.J. Abrams bring with him an unconscionable crosspollination from the Star Trek franchise? In short, will Star Wars survive its metamorphosis to the post-Lucas era? The story continues…

Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens (if we may be allowed a scrolling preamble) has been released with considerable fanfare and after much anticipation. Like the birth of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, its arrival brings together a nation of fans united in pride, patriotism, hope and nostalgia (and, be warned, young George, with a bevy of concealed weapons held at the ready). At last! A renewal of the franchise that blew up the box office in 1977 and grew quickly to become – for some people quite literally – a cinematic religion. But those who queue for midnight screenings do so with some trepidation. Given the false dawn of the prequelogy (Episodes I–III), will this merely be more of the tepid same? How will the new film tie in with the Expanded Star Wars Universe? Will the original characters return and stay true to memory three decades on? Will director J.J. Abrams bring with him an unconscionable crosspollination from the Star Trek franchise? In short, will Star Wars survive its metamorphosis to the post-Lucas era? The story continues…

Monday, 21 March 2016

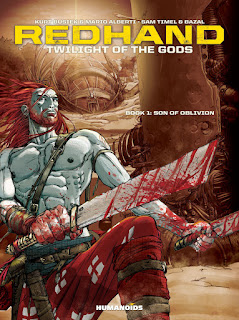

Redhand: Twilight of the Gods, Book 1: Son of Oblivion, by Kurt Busiek and Mario Alberti (Humanoids) | review

A party of highly religious, spear-carrying hunters stumble across a strange place while fleeing Kiotha slavers. It contains many dead bodies suspended in liquid within green tubes. But as the slavers attack, it turns out that one of the men in the tubes lives! He emerges naked, and fights mindlessly, but elegantly, like an automaton. Afterwards, his first words to the hunters become his name, because he doesn’t know who he is: “Red… hand…” Returning to their home, he faces the usual problems of the man with no name after the battle is done: hardly anyone wants him to stick around – except the pretty girl, and she has a jealous and angry admirer. This is a beautifully drawn graphic novel, every panel full of detail and interest. The story is one we’ve heard before, but it never gets old, and this version takes some surprising turns as it progresses. This should appeal greatly to anyone who yearns for new stories in the style of the early Elric books. Stephen Theaker ****

Friday, 18 March 2016

Stoker’s Manuscript, by Royce Prouty (G.P. Putnam’s Sons) | review by Jacob Edwards

Neither fading nor impaling into insignificance.

There are numerous ways to kill a vampire; somewhat fewer to keep him dead. Many a blood-curdling tale has been told. But the modern brow frowns upon capital punishment, so nowadays we prefer neutering (in the sense of making something ineffective). We strap vampires to the operating table and infuse them with a ghastly blend of garlic sauce and teenage hormones. We turn them into that which they most despise.

There are numerous ways to kill a vampire; somewhat fewer to keep him dead. Many a blood-curdling tale has been told. But the modern brow frowns upon capital punishment, so nowadays we prefer neutering (in the sense of making something ineffective). We strap vampires to the operating table and infuse them with a ghastly blend of garlic sauce and teenage hormones. We turn them into that which they most despise.

Monday, 14 March 2016

The Red Seas, Book One: Under the Banner of King Death: The Complete Digital Edition, by Ian Edginton and Steve Yeowell (Rebellion) | review

Captain Jack Dancer got his ship by leading a mutiny, outraged by the mistreatment of the crew. Now he leads them to adventure on the high seas. They are treated a bit better, but their chances of survival haven’t improved. This book collects three of their adventures. In the first they must do battle with Dr Orlando Doyle, a hollow man with a crew of the dead. In the second they meet Aladdin, in search of Laputa and still giving orders to his genie, and in the third they travel deep within the earth, where a beautiful empress rules a race of lizard men. Three other stories feature people met by Jack Dancer on his travels: Sir Isaac Newton (his life secretly extended by the Brotherhood) fights a British war criminal possessed by an ancient Roman demigod; the two-headed dog Erebus (having left one head at home) and a friend hunt hidden treasures in blitz-torn London; and the regulars of Jack’s favourite watering hole must deal with a fellow who is “much more than a man… and a little less than God”. It’s three hundred and seventy pages of unapologetic adventure, made all the more satisfying by being drawn in its black-and-white entirety by Steve Yeowell. (I still remember how disappointed I was when I realised he wouldn’t be illustrating the whole of The Invisibles.) The stories were originally serialised in brief episodes in 2000 AD, but apart from Isaac Newton’s werewolf fight (which features little diary recaps) they are seamless, each of the three main stories reading like a short graphic novel. It’s a digital-only collection, so look out for it in the 2000 AD app and places like that. Stephen Theaker ***

Friday, 11 March 2016

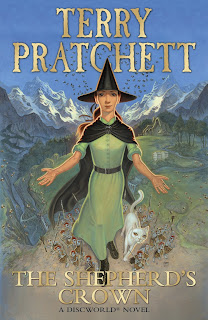

The Shepherd’s Crown, by Terry Pratchett (Harper) | review by Jacob Edwards

A Wickerword basket.

Terry Pratchett – author and humorist; a writer of such immense popularity, his books for many years topped Britain’s most-stolen tally; the man who armed Death with laconic wit and a scythe and made him a recurring character – is dead. This of course was inevitable. THERE CAN BE NO EXCEPTIONS. But for all that Pratchett’s passing will leave a vacuum to be filled in the New York Times bestseller lists and the reading lives of millions of devoted followers, let us not mourn overmuch; rather, we should cherish the years he gave us and scrump one last time from the verdant pages of a new Discworld novel: a gentle, bittersweet celebration.

Terry Pratchett – author and humorist; a writer of such immense popularity, his books for many years topped Britain’s most-stolen tally; the man who armed Death with laconic wit and a scythe and made him a recurring character – is dead. This of course was inevitable. THERE CAN BE NO EXCEPTIONS. But for all that Pratchett’s passing will leave a vacuum to be filled in the New York Times bestseller lists and the reading lives of millions of devoted followers, let us not mourn overmuch; rather, we should cherish the years he gave us and scrump one last time from the verdant pages of a new Discworld novel: a gentle, bittersweet celebration.

Wednesday, 9 March 2016

Olympus, Book #1, by Geoff Johns, Kris Grimminger and Butch Guice (Humanoids) | review

Professor Walker and her assistant Brent are on a dive, ten miles off the coast of Thessaly, when they discover a sunken galley, and inside the galley a sealed trunk. Back on board their ship, the Desmon, with student sisters Rebecca and Sarah, they must decide whether to open it. The right thing to do would be to notify the Greek authorities, but Brent reminds the professor of the dean’s plan to close the archaeology department… They open it, and inside is an ancient urn, bearing the inscription, “Herein contains the misfortunes of man.” Could it be Pandora’s box? Even as they think about that, a storm whips up around them, just in time to accompany a gang of gun-toting pirates who expect to find diamonds on board. The storm doesn’t stop till the Desmon is washed up on the shores of a paradise island, with a giant statue of naked Zeus on the beach. More adventures ensue! This is a very good-looking book, Dan Brown’s colouring looking especially good in the digital format. Bikini-wearing Sarah’s tendency to find a new pose for each panel seems a bit cheesy, but the mysterious island is as spectacular as the plot needs it to be. The central idea is interesting, even if the way events play out, at least in this first book, is the same as any number of films – the book feels like it was made with both eyes on Hollywood. The story stops on a cliffhanger (when most of the characters are asleep), so it doesn’t feel like a complete album in itself, but it’s still very enjoyable. I especially liked the sound effect used here when a guy gets punched in the jaw: “PLAF!” Stephen Theaker ***

Monday, 7 March 2016

Gods of Egypt | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Dumb. One-dimensional. Loved it.

If you like epic fantasy action films that seem conceived by seventh grade boys, then Gods of Egypt is for you. “Look, Johnny: you can remove the smartest god’s brain and it’s blue. It sparkles too. Then you can put it in your own head and you get smarter!”

If you like epic fantasy action films that seem conceived by seventh grade boys, then Gods of Egypt is for you. “Look, Johnny: you can remove the smartest god’s brain and it’s blue. It sparkles too. Then you can put it in your own head and you get smarter!”

Friday, 4 March 2016

Savages, by K.J. Parker (Subterranean Press) | review by Jacob Edwards

“The end of the world began with a goat…”

Savages, for want of better terminology, is a down-to-earth epic historical fantasy wherein a once-mighty empire hangs in the balance, its waning existence threatened by not-so-proverbial (in fact, ever-so-practical) barbarians at the gate. K.J. Parker threads together several storylines in exploring this scenario, primary of which are those of Raffen, a chieftain whose loss of identity affords him freedom to turn his hand to any craft; Calojan, an imperial general with a self-fulfilling reputation for invincibility; and Aimeric, a pacifist turned arms-maker and politician, upon whose wiles may rest not only the future of the city but also a watertight case for prosecution by cosmic irony. Parker avoids playing favourites, and so each player holds the reader’s sympathies in conjunction with the spotlight, this perspective switching subtly whenever one is placed in opposition to another. Such protagonistic ambiguity – a load-bearing device that feeds credence back into the narrative mechanism – is a feature of Parker’s novels, and allows the possible storylines to unfold without prejudice. Whatever happens will happen.

Savages, for want of better terminology, is a down-to-earth epic historical fantasy wherein a once-mighty empire hangs in the balance, its waning existence threatened by not-so-proverbial (in fact, ever-so-practical) barbarians at the gate. K.J. Parker threads together several storylines in exploring this scenario, primary of which are those of Raffen, a chieftain whose loss of identity affords him freedom to turn his hand to any craft; Calojan, an imperial general with a self-fulfilling reputation for invincibility; and Aimeric, a pacifist turned arms-maker and politician, upon whose wiles may rest not only the future of the city but also a watertight case for prosecution by cosmic irony. Parker avoids playing favourites, and so each player holds the reader’s sympathies in conjunction with the spotlight, this perspective switching subtly whenever one is placed in opposition to another. Such protagonistic ambiguity – a load-bearing device that feeds credence back into the narrative mechanism – is a feature of Parker’s novels, and allows the possible storylines to unfold without prejudice. Whatever happens will happen.

Slow Bullets, by Alastair Reynolds (Tachyon Publications) | review

There was a war between the Central Worlds and the Peripheral Systems, both of them fairly religious, and just as a peace was agreed Scurelya Timsuk Shunde, our narrator, is captured by a war criminal and taken to a bunker, where he injects her with a slow bullet, which’ll burrow through her body till it reaches her heart. She’s left to die, and probably will, and then she wakes up…

Wednesday, 2 March 2016

Barbarella, Book 1, by Jean-Claude Forest (Humanoids) | review

I’m always amazed at how little I like the film Barbarella, given how much I generally adore that kind of sci-fi from the sixties and seventies. I think the problem is just that it’s dull. This is not a charge you could level at the original comic book, presented here in a new English-language adaptation by Kelly Sue DeConnick of Captain Marvel fame. It’s too random and fast-moving to be dull, bouncing from one over-the-top scenario to another like a hyperactive moon-man. Barbarella is a space traveller whose tried and trusted approach to danger is to take off all her clothes, though to be fair that usually works out for her, and she’s uncynical about using her charms that way. She’s spaced-out, disengaged, lusty, bisexual, and looks a lot like Brigitte Bardot. Her adventures in this first book include encounters with flower growers under siege, a face-thief, a hunter and the scientist who creates monsters for him to fight, the Princesses of Yesteryear and my personal greatest fear, flying sharks! At its best it reminds me of our own much-missed Newton Braddell, and even at its worst it’s enjoyable. Despite the sauciness, it doesn’t feel adult in tone. In art and narrative style it reminds me rather of the lightweight, sketchy stories that would appear in children’s annuals from the sixties, like those for Doctor Who and Bleep and Booster, just with rather saltier content in places. It ends very abruptly, but that feels okay. It’s not the greatest comic you’ll ever read. I do think it’s worth reading. Stephen Theaker ***

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)